Looking for Walter Landor Dickens

Contributed by Christian Lehmann, Bard High School, Early College

On his 52 birthday (7 February, 1864) Charles Dickens received word that his son, Walter Landor, had died in India on 31 December 1863. A few days later Dickens described the circumstances of Walter’s death in a long letter to Angela Burdett Coutts (12 February 1864). “On the last day of the old year at a quarter past 5 in the afternoon he [Walter] was talking to the other patients about his arrangements for coming home, when he became violently excited, coughed violently, had a great gush of blood from the mouth, and fell dead;—all this, in a few seconds. It was then found that there was extensive and perfectly incurable aneurism of the Aorta, which had burst.” He continues, “Another of his brothers, Frank, I sent out to Calcutta on the 20th of December. He would hear of his brother’s death, on touching the shore.” Dickens spends much of the remainder of the letter dwelling on the coincidence that he was playing charades at the time of his son’s death and had a funereal presentiment about the costume he had created. In a letter to Charles Knight on the first of March 1864, Dickens seems to have settled upon the details that he is willing to share, namely, the sanguinary and rapid demise of his son and Frank’s macabre arrival. “He was talking to some brother-officers…when he suddenly became excited, had a rush of blood from the mouth, and was dead. His brother Frank would arrive out at Calcutta, expecting to see him after six years, and he would have been dead a month.” The narrative of Walter’s afterlife ends here, but a year ago, around Christmas of 2018, I would pick it up again.

On December 26th, 2018, in a Twitter response to @hemantsarin posting an article from The Tribune India about Walter Landor Dickens’s grave in Kolkata (Calcutta), the prominent Victorian twitter handle and website, @VictorianWeb, wrote, “Hope someone visits one day. Sad!”

At the time, @Southportgal (Rochelle Almeida) had been spending a year in India and tweeting about her experience so I asked if she might see it. Unfortunately, I had missed the window.

Well, this planted the seed of an idea in my head, and when I was invited to a wedding in Chennai (Madras) over the second week of December 2019, I decided to let the idea flower. I would visit the grave and honor Walter near the time of his death day (31 December) and deliver the flowers that The Tribune said no one had placed for “poor Walter Landor Dickens, whose desolate tombstone remains desolate even on a Christmas day. No caring hand places flower on it” (Link).

Walter Landor Dickens, called Wally by some and “Young Skull” by his father due to his high cheekbones (Pilgrim Letters 3:331) was born on 8 February 1841. Originally to be called Edgar, his father changed his mind and named him after the poet Walter Savage Landor, upon whom, in turn, Dickens claimed to have based the character of Bleak House‘s Lawrence Boythorn: “Boythorn is (between ourselves) a most exact portrait of Walter Savage Landor” (to Mrs. Richard Watson, 6 May 1852; Pilgrim Letters 6:666). He is the baby with the plumed hat in Daniel Maclise’s (1841) famous painting of the first four Dickens children and the second Grip.

Walter passed the next years of his life relatively without incident, other than winning a variety of medals in school and once, when he was twelve, spending the day in the bathroom in solitary (1857) confinement after having thrown a chair at a nurse. At the age of sixteen and with the help of Angela Burdett Coutts, he obtained a Cadetship and was off to Calcutta with the East India Company’s Presidency armies. There he passed a relatively unremarkable career that showed a propensity for getting into debt. In late 1863, he turned most of his possessions into cash with the aim of returning home, but died before he could. Instead of his body, Dickens received his debt(for a fuller biography, see VictorianWeb Link, Lucinda Hawksley Dickens’s Artistic Daughter, Katey, and Robert Gottleib, Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens).

As a few different popular sources have mentioned (The Hindu, Culture Tripand Get Bengal), Charles’ son was originally buried in a military cemetery in Bhowanipore, not far from where the tombstone now lies. In 1987, a group of students of Jadavpur University raised funds to move the tombstone(but not the body) to South Park Street Cemetery where other notable European emigrants are buried. This task is commemorated by a small plaque beneath the tombstone: “this tombstone from Bhowanipore Cemetery was placed here in April 1987 helped by collections made by the students of Jadavpur University.” Further upkeep from that point seems negligible.

I arrived in Calcutta on the 22nd of December on an all-night train from Puri to Howrah, the main train depot for Calcutta and home to some phenomenal Victorian architecture. After taking one of the ubiquitous yellow Ambassador Classic taxis to my hotel, I set out to find the South Park Street Cemetery. This was the easiest part of the journey, it would turn out, since it is relatively famous and shows up promptly on GoogleMaps.

When I got to the cemetery, I paid my 50 Rupee fee, signed my name, and proceeded to wander around in search of the grave. The first thing I noticed was the abrupt silence as large walls cut the site off from the incessant honks, murmurs, roars, and bellows of the street. Secondly, I realized that this would be a fairly difficult task as my eyes drank in the lofty mausoleums all around me.

Luckily, The Hindu had printed this image.

I therefore knew that I was not going to be looking for any of the empyreal edifices, but would instead have to conjure the spirit of Durdles to navigate this labyrinth of funerary markers. I set off and searched among the centuries-old concrete and marble monuments and crept by the young locals gathered for dates, conversation, and photoshoots.

After making a few rounds of the cemetery and watching the sun’s shadows lengthen across the text of the tombs, I began cutting across and behind the designated walking paths, some of which were already turning eldritch.

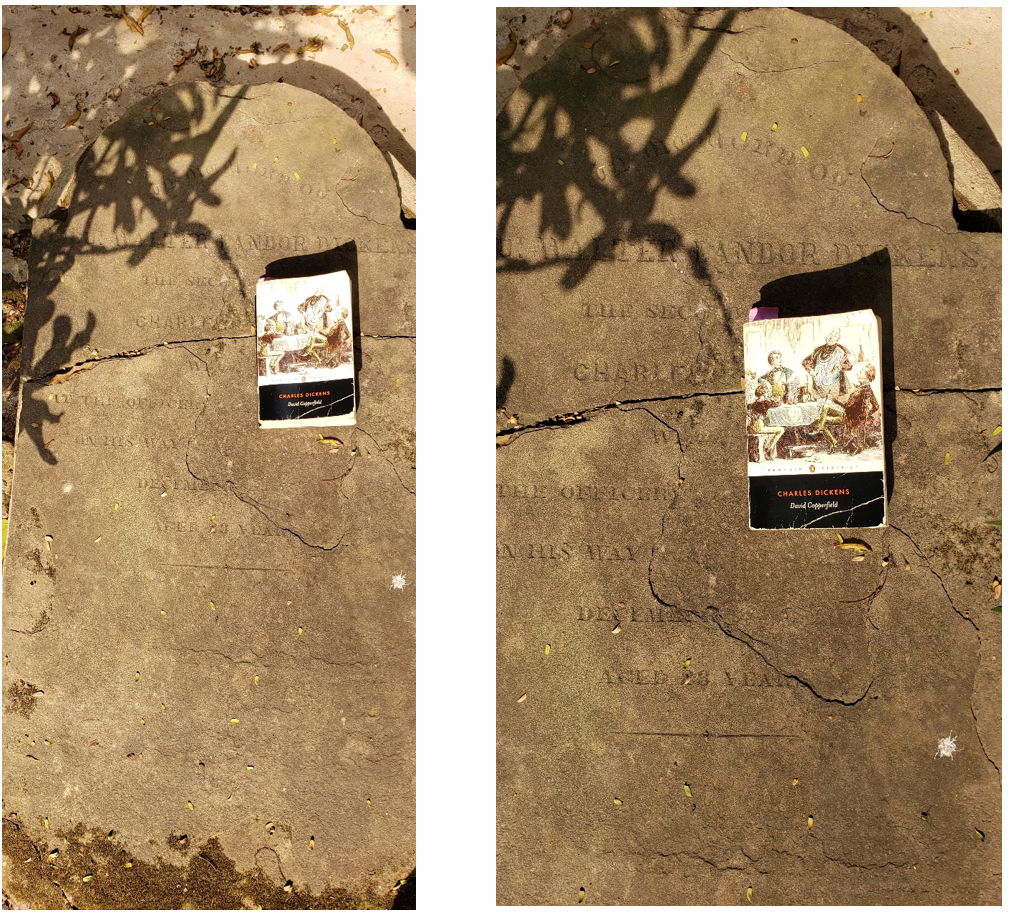

It was only on my final, and somewhat frantic, scramble moments before I needed to leave that I stepped behind a corner mausoleum and caught sight of the chipped and fragmentary tombstone of nondescript marble that I had seen online.

Here, nestled between two small shrubs and dominated by someone else’s massive memorial, lay the reason I had traveled from Cleveland, Ohio to Kolkata, India: Walter Landor Dickens’ tombstone. I did not have flowers, but I had brought my copy of David Copperfield along, and so I put father and son together.

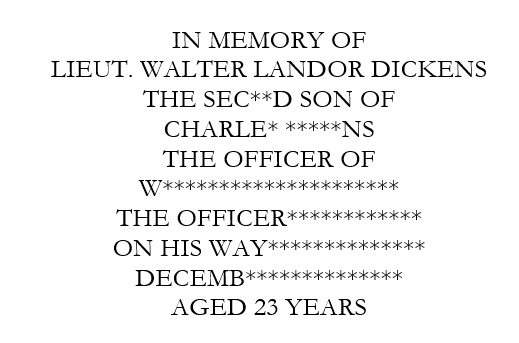

The text of the tombstone is difficult to read, and a large piece of it has broken away, which is oddly fitting given the fragmentary knowledge that we have about Catherine and Charles’ fourth child.

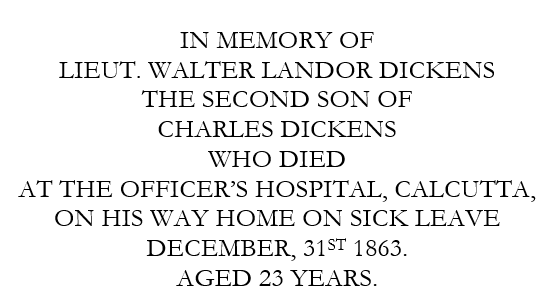

A much earlier account, from 1914, of a similar pilgrimage (p.128 of this article by Wilmont Corfield, although he normalizes the capitalization pdf), reveals that it read in full:

My pursuit of the grave was hardly the dramatic nocturnal event that Corfield’s was. In desperation to find the grave he had heard about before leaving Calcutta, he had put forth “urgent enquiries.” In response, he learned that “an aged Bengali had remembered seeing a number of sahibs standing round a grave in a certain part of the cemetery in the sixties. A close search by lantern light had followed and the stone lay revealed. Weeds and debris brushed aside, the havoc of earthquake, sun and rain had yielded to the searchers, and disclosed the hidden secret of the years” (ibid).

The next day I decided to return and spend a more leisurely afternoon with the tombstone. I also wanted to make it easier for the next person who seeks it out. Upon passing through the gate, paying the fee, and writing your name, take the first right.

Walk until you come to the large white marble structure on your left.

Step behind it, and you will find Walter’s tombstone.

I pulled out my copy of David Copperfield and read Dickens’s most extensive passage on Calcutta in all of his writings. (The only other mention of the city is a throw-away comment in chapter 31 of Martin Chuzzlewit, “Many a man in Mr Pecksniff’s place, if he could have dived through the floor of the pew of state and come out at Calcutta or any inhabited region on the other side of the earth, would have done it instantly. Mr Pecksniff sat down upon a hassock, and listening more attentively than ever, smiled.) The passage in Copperfield reads:

But Mr. Mills, who was always doing something or other to annoy me—or I felt as if he were, which was the same thing—had brought his conduct to a climax, by taking it into his head that he would go to India. Why should he go to India, except to harass me? To be sure he had nothing to do with any other part of the world, and had a good deal to do with that part; being entirely in the India trade, whatever that was (I had floating dreams myself concerning golden shawls and elephants’ teeth); having been at Calcutta in his youth; and designing now to go out there again, in the capacity of resident partner. But this was nothing to me. However, it was so much to him that for India he was bound, and Julia with him; and Julia went into the country to take leave of her relations; and the house was put into a perfect suit of bills, announcing that it was to be let or sold, and that the furniture (Mangle and all) was to be taken at a valuation.

(DC, Ch. 41, p. 596-597 Penguin)

Closing my book, I decided to fulfill my last task and place flowers upon tombstone. I walked the cemetery and selected from the meager floral growth there. At last I placed my bouquet.

In searching for the flowers, however, I had also come upon a plastic garland cast away in a refuse heap. So I decided to go all out and give Walter a gaudy presentation and to celebrate him in a way I imagine he never was, even when he departed England at sixteen years old.

[…] On his 52 birthday (7 February, 1864) Charles Dickens received word that his son, Walter Landor, had died in India on 31 December 1863. A few days later Dickens described the circumstances of Walter’s death in a long letter to Angela Burdett Coutts (12 February 1864). “On the last day of the old year at a quarter past 5 in the afternoon he [Walter] was talking to the other patients about his arrangements for coming home, when he became violently excited, coughed violently, had a great gush of blood from the mouth, and fell dead;—all this, in a few seconds. It was then found that there was extensive and perfectly incurable aneurism of the Aorta, which had burst.” (Source: The Dickens Society) […]