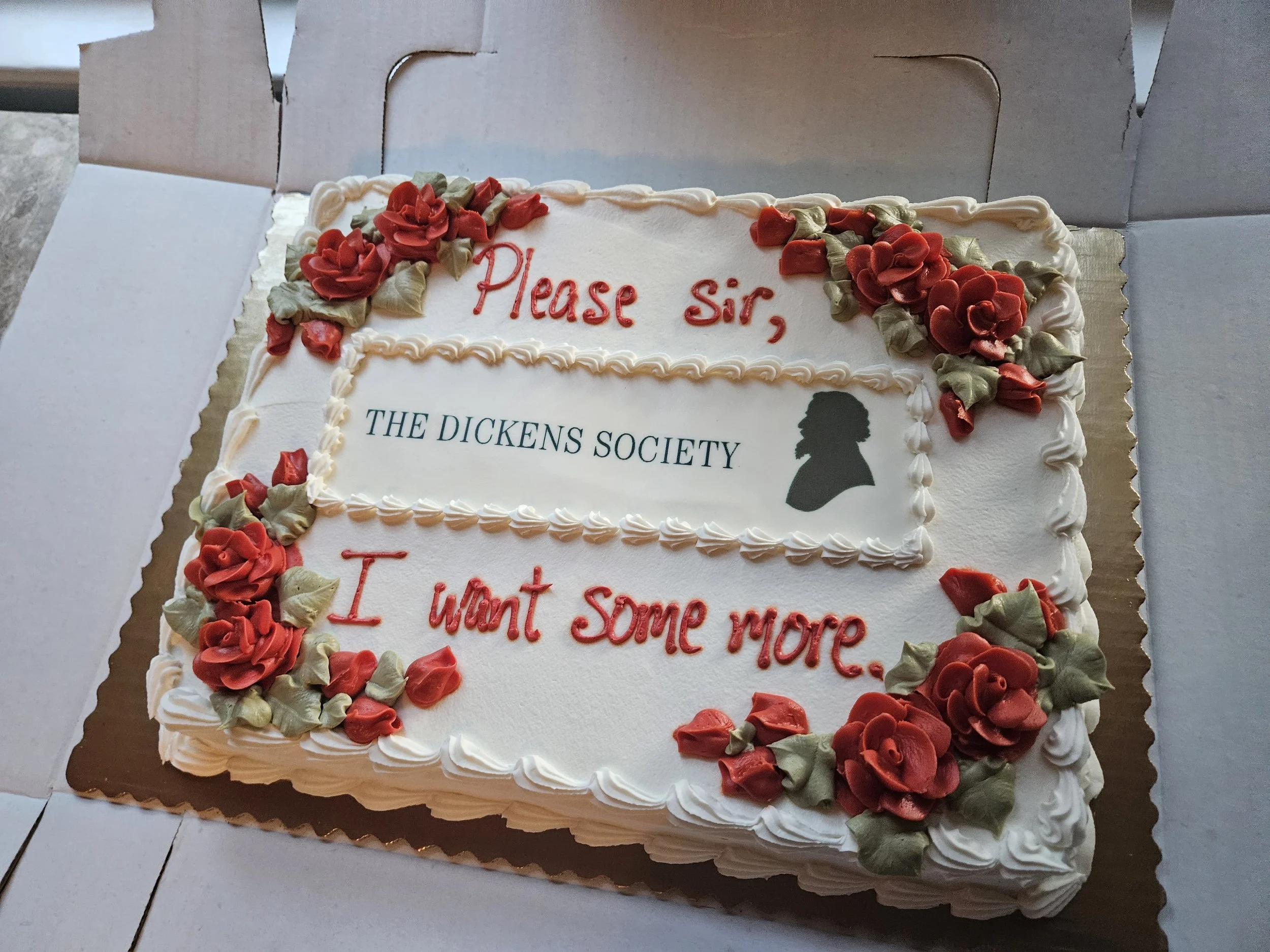

Our Mission

To conduct, further, and support research, publication, instruction, and general interest in the life, times, and literature of

Charles John Huffam Dickens

(7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

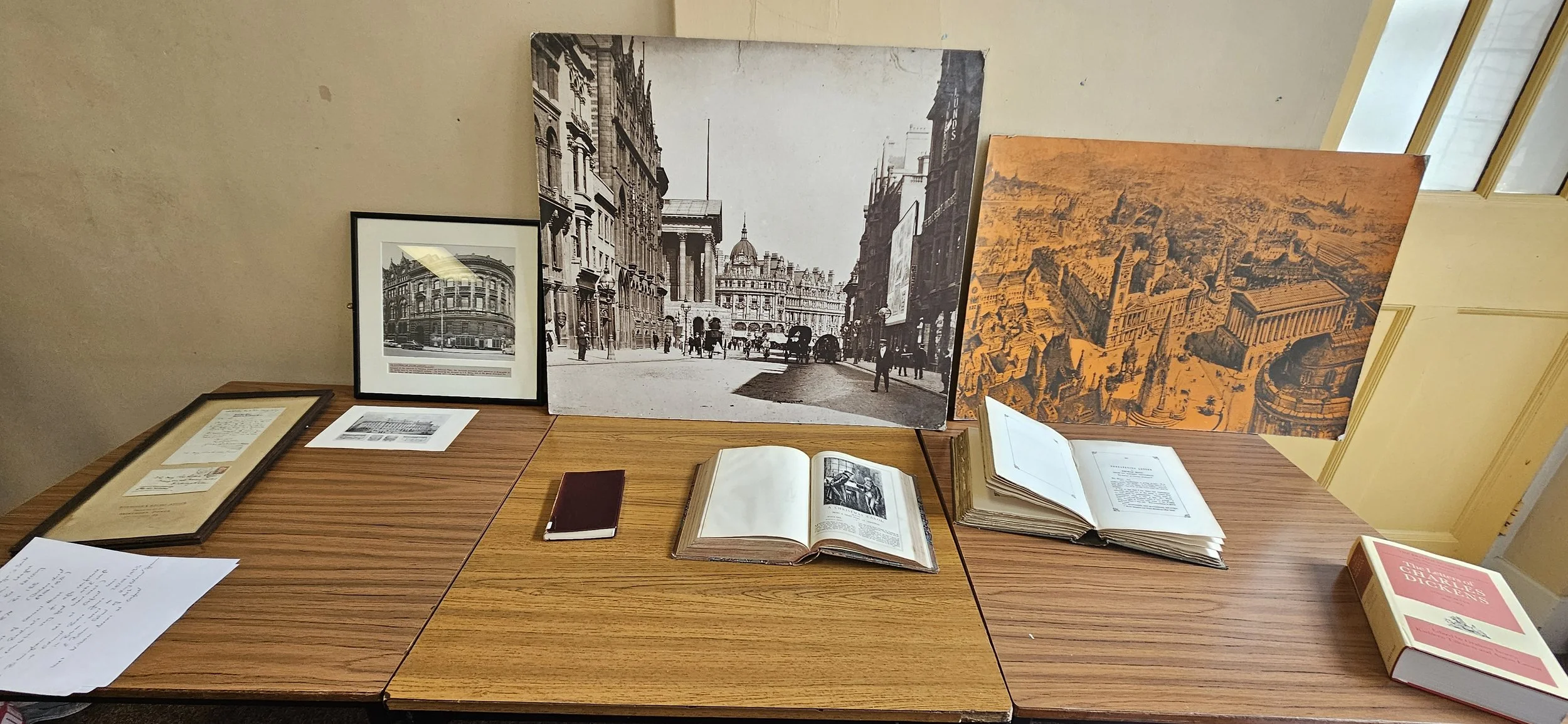

Our History

The Dickens Society has a global reach, with hundreds of members hailing from no fewer than 21 countries in North and South America, Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and Australia.

Members of the Dickens Society range from university professors, lecturers, and adjunct faculty to graduate students, independent scholars, and enthusiasts. They may apply to present papers at our annual symposium, an event prioritising egalitarianism in research, and receive special announcements and updates through our Dickens Society members listserv.

Additionally, other featured events for members include Dickens Society sponsored panels at MLA and regional MLA conventions. Membership comes with an individual subscription to the Society’s journal, Dickens Quarterly.

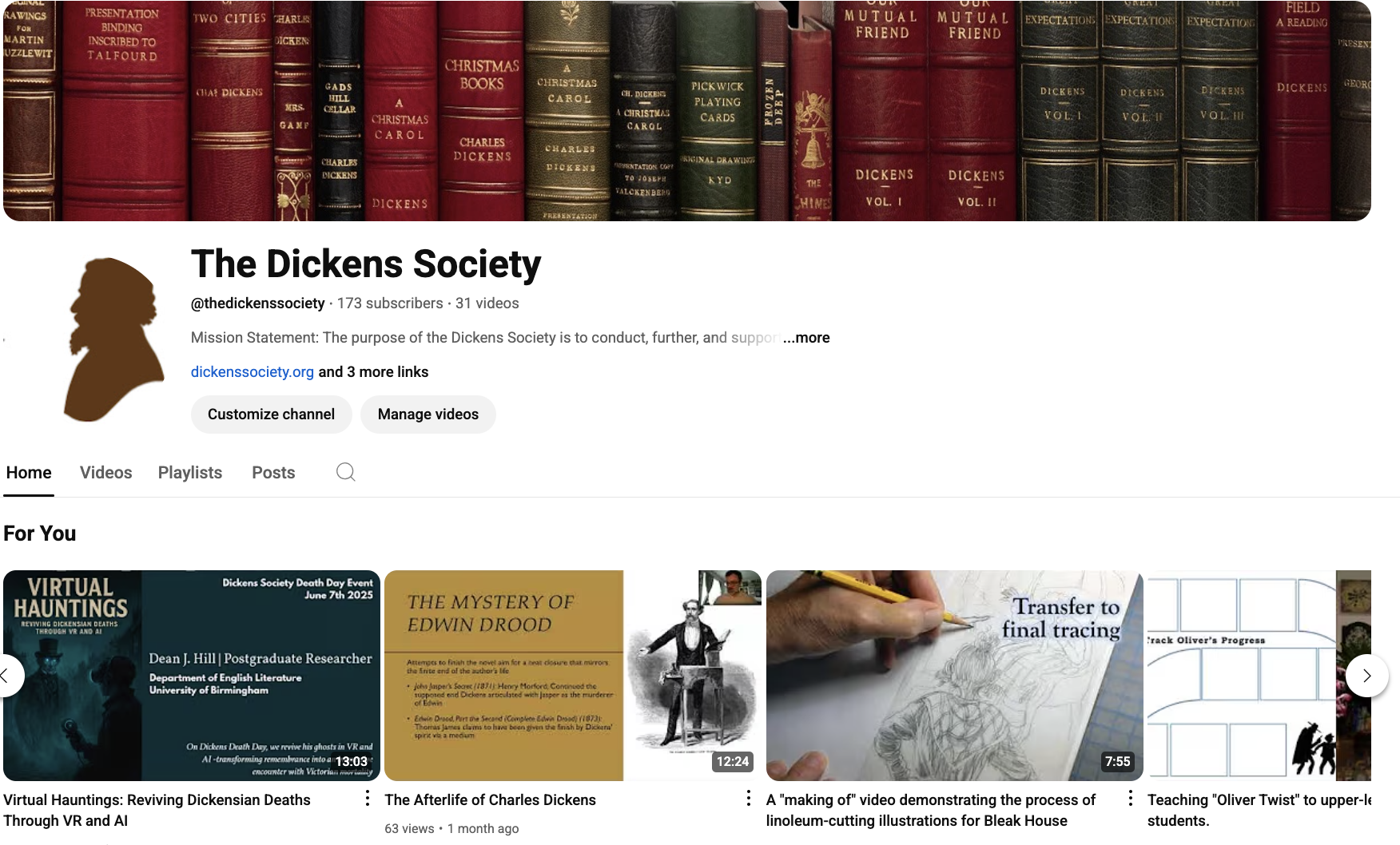

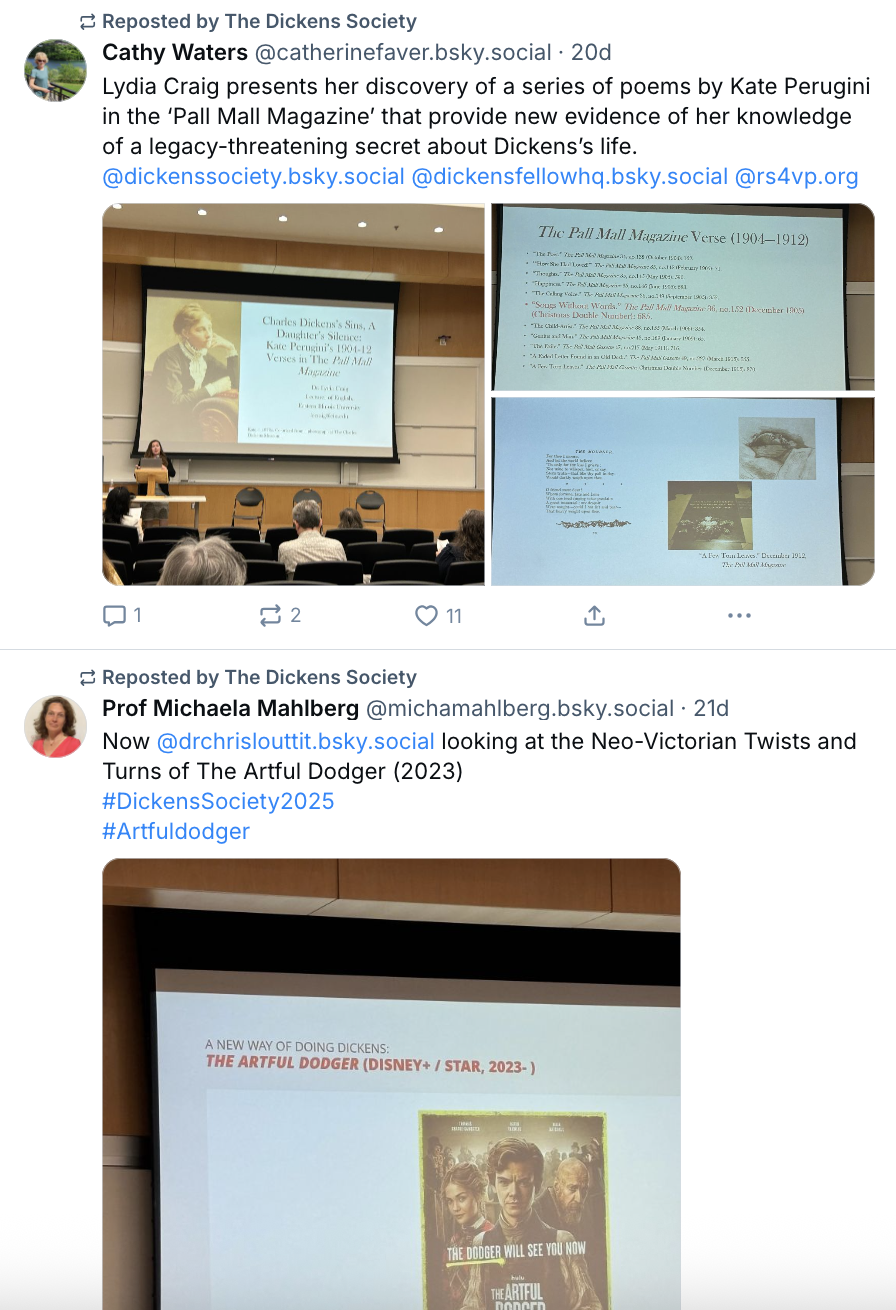

Follow The Dickens Society on social media!

Instagram: @the_dickens_society

YouTube: @thedickenssociety

Bluesky: @dickenssociety.bsky.social

![C. Natkins. [Photograph of Charles Dickens sitting at table with book], photograph, 1861.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6893b0af13cef27754e96a9b/2e6814d3-b28b-4ea8-9510-b27af2e2c460/Dickens1861Portrait.jpg)