Boz Reinvented: the Many Modern Faces of Charles Dickens

This post has been contributed by Katie Bell, in response to the 22nd annual Dickens Society Symposium, held in Boston, 14-16 July 2017. Read the storify from the conference here: Day One, Day Two, and Day Three. Read her first post for the Dickens Society Blog here.

How do we remember Dickens? There is the historical figure whom none of us in the modern era can ever truly know, who led a complicated life in the limelight, filled with a love/hate relationship with the press and the uphill battles he fought to undo social injustices. Then there is the fictional Dickens, The Man Who Invented Christmas (or so the forthcoming film would have us believe), whom some readers come to feel is the unnamed narrator behind the works we so cherish. Through this connection of author and reader, we feel we know him. Recent research has been published by Holly Furneaux on this concept of the felt relationship. Furneaux writes: the idea that “Dickens’s characters are personal friends is a common, and widely documented one” (124).[1] This felt relationship extends to the author himself and bleeds into how we utilize the historical Dickens and his works in the modern era. Dickens evolves into becoming synonymous with Victorian London, the comforts of an English home and many times, the macabre and elusive spiritual world. Thus, when he appears in modern works such as the video game Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate (2015), the cameo does not feel incongruous with the Dickens we feel we know. This type of relationship with Dickens and his works was explored in one of the last panels of the conference titled “Dickens’s Afterlives.”

Emily Bell began by invoking the idea of reusing Dickens as a character in her paper titled, “Fictional Dickenses, 1849-2015.” Citing all of the more recent incarnations of fictional Dickenses such as in Doctor Who, The Invisible Woman, and Assassin’s Creed, she examined how we began to create a fictional Dickens from his published letters to Maria Beadnell in 1908. Shortly after, his affair with Ellen Ternan was brought forth in the 1920s, and the public adapted this into their persona of Dickens as well, crafting a somewhat rocky impression of his relationship with women. We also have positive creations of Dickens, Bell explained, such as a great sense of his imagination and authorial power from the account his daughter Mamie wrote of him in My Father, As I Recall Him (1896), in which Mamie explains the great facial pantomime her father practised in front of a mirror before drafting. Bell ended her talk by provoking the idea that in Assassin’s Creed, we see Dickens as a non-playable character who gives us missions to accomplish. He is “a touchstone that brings authority to the story” of the game itself. This concept is indicative of the way in which we view Dickens: not that he is a non-playable character, but that there are rules which must be followed in order for the character “Dickens” to appear authentic. Further, for one to evoke him, he/she must follow culturally accepted norms of what it means to be Dickensian.

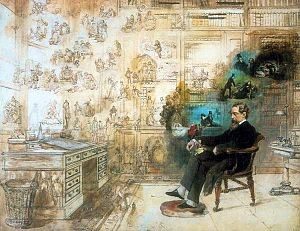

This ending thought blended well into Temitope Abisoye Noah’s paper, “Dickens and Parapsychology in Eastwood’s Hereafter” which discussed the Clint Eastwood film of 2010. In this film, Dickens is also a character, but through audio recordings of his works. Noah explained that the main character of the film is a psychic reader who meditates on narrated recordings of Dickens’s works, and the film often cuts to Dickens’s portrait which gives the impression that he is in the room with the other characters, although perhaps as a ghostly figure. George (played by Matt Damon) eventually visits the Charles Dickens Museum in London and views Robert Buss’s painting Dickens’s Dream (I spent several years at the CDM as a volunteer and can attest to the museum’s felt relationship to Dickens and his family), and what evolves in the film is a connection between the psychic reader George, who hears ghosts, and Dickens, who is presented as hearing the characters of his imagination. Noah concluded with the idea that the thesis of Hereafter is that interaction with “the other” (of Freudian terminology) can be an instrument of healing. Dickens held a fascination with ESP and was a practiced mesmerist himself. Although not factually a member of The Ghost Club as the video game Assassin’s Creed would claim, Dickens held a long-standing relationship with the supernatural, and the connection between the physical and the non-physical world is explored in a very gentle way in Eastwood’s film.

Joseph McLaughlin explored the concept of adapting the term “Dickensian” to progressive politics in his paper, “The Contemporary Progressive Movement: A Dickensian Approach.” McLaughlin explored the idea of the moral historical figure Dickens being evoked by politicians to “make poverty palpable,” which, McLaughlin stated, was what Dickens did very effectively in his works. “He gives a vivid description paired with horror, a bait and switch” McLaughlin said, which is what allows for his settings, such as Tom-All-Alone’s in Bleak House or Fagin’s Den in Oliver Twist, to be Dickensian. McLaughlin referenced the political cartoons of Thomas Nast and F. T. Richards which depicted Dickensian scenes of children enduring poverty and abuse by up and coming politicians. The below cartoon by Nast depicts William M. Tweed, who as the head of a political organization in New York City was able to defraud the city of upwards of 200 million dollars. In the Nast cartoon, Tweed and his cronies are throwing out the text books by Harper’s and replacing them with their own, as well as throwing punches at the young boy in the foreground.

McLaughlin explained how the imagery of Dickensian children enduring such poverty and abuse as is referenced in the Nast cartoon were a very real form of political propaganda beginning from the latter half of the nineteenth century. Even modern politicians such as American President Lyndon B. Johnson and Democratic Party hopeful Bernie Sanders evoked such imagery in their campaign bids. McLaughlin stated that the connection between Dickens and these politicians of more socialist leanings was that they all adamantly believed in a “collective cost of poverty which is paid by everyone…To be Dickensian is not just to recognize hypocrisy, but to frame it with egalitarian change.”

The final paper was given by Maya Zakrewska-Pim and was concerned with adaptations of Oliver Twist in young adult fiction. Zakrewska-Pim’s paper, “Charles Dickens and Children’s Literature: Oliver Twist Adapted” discussed how most audiences are culturally aware of Twist even if they have never read the original text itself, and that this lends itself to an adaptation. As has been stated on the documented idea of felt relationships, because we feel we know Oliver, his reappearance in other texts (outside of his own original one), appears authentic to us, as long as certain rules of evoking him are followed (meaning that he appears “Dickensian”). Zakrewska-Pim referenced the adaptation Oliver Twisted: or The Witch-Boy’s Progress by J. D. Sharpe, whose cover art draws on the young adult series Goosebumps by R. L. Stine, and in which Oliver becomes something of a ghoul hunter or a John Constantine figure, ferreting out evil entities in the orphan house in which he lives. Zakrewska-Pim explained that adaptions are necessary to introduce the classics to a “wider public,” just as these works were originally disseminated when they were published through serialisation. The orphanage in which Oliver lives is run by werewolves and ghouls, and is a parody of Dickens’s London: the rich thrive while the poor suffer. Fitting in well with themes referenced in McLaughlin’s paper, the thesis of Zakrewska-Pim’s work is that while this parody is a fun horror adaptation of the original piece for a newer young adult audience, it also succeeds in being an independent novel in its own right. The new audience reading Oliver Twisted understands that it is an adaptation of the original, but brings into focus, in a humorous way, the themes Dickens strove to address in his original work, such as the struggle of the poor. Sharpe brings into focus through the young adult horror fiction genre the disadvantaged lives of the poor, and to what extent the wealthy are able to profit off of them.

“Dickens’s Afterlives” brought together an assortment of different ways in which Dickens and his works are remembered and recycled. All four of the papers examined to what scope we feel we know Dickens, and how this felt relationship fits in with our understanding of his body of work itself. Ultimately, Dickens has become a figure to be referenced when a work is trying to draw on ideas of those who are disadvantaged, or who are social outsiders. Additionally, he is who we evoke when we think of mid-Victorian London; we look to his descriptions of the fog, the grime and the dirt of the city, and we find ourselves magically transported to the London of his era. Dickens becomes our tour guide to an age which no longer exists but to which we can be transported through adaptations, film, art and his original works themselves.

[1] Furneaux, Holly. “(Re) Writing Dickens Queerly: The Correspondence of Katherine Mansfield.” Reflections on / of Dickens, edited by Ewa Kujawska-Lis and Anna Krawczyk-Laskarzewska, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014, pp. 121-137.

Katie Bell is a PhD student at the University of Leicester. Her thesis is titled “The Diaspora of Dickens: Death, Decay and Regeneration”, the focus of which is the intertextuality of Dickens’s works and 20th century American texts of the Southern Gothic genre. The American authors examined in her thesis are William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and Carson McCullers. She is based Atlanta, Georgia where she is also a volunteer docent for The Wren’s Nest, the home of Atlanta author Joel Chandler Harris most famous for his ‘Br’er Rabbit’ tales. She can be found on Twitter @decadentdickens.