After Dickens: His Influences in Fiction 1879-1914

This piece is contributed by Tom Hubbard, a former Lynn Wood Neag Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Connecticut and Professeur invité at the University of Grenoble. He has been an Honorary Fellow at the Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Hubbard’s article Heart and Soul: Dickens and Dostoevsky appeared in the online journal Slavonica in 2020. He is now retired, and this is his first blog post for the Dickens Society.

Dedicated to the memory of K.J. Fielding

Dickensian themes – with variations

In 1865, a young Henry James reviewed Dickens’s new novel, Our Mutual Friend. He was ruthless in his criticisms. Dickens’s success, he maintained, was based on “the manufacture of fiction,” and Our Mutual Friend was “lifeless, forced, mechanical” (Selected Literary Criticism 31-32).

James was signalling a turning point in the history of the novel, from formulaic Victorian fiction towards the more consciously artistic and intellectual tendencies of early modernism. However, James himself would produce, in 1886, The Princess Casamassima, a novel set partly in the dingiest parts of London; it’s his most “Dickensian” work. The older writer was just too powerful to dismiss altogether.

Indeed, Dickens’s literary descendants represented both departure from and engagement with the master. Little Dorrit provides a test case: Daniel Doyce is the brilliant and stoical inventor who is neglected in his native England but who finds recognition abroad. It is here that Dickens anticipates something of the turn of the century Zeitgeist; Doyce is a character type that Dickens’s successors would take up and modify in their own work. Doyce’s attitude to his work is one of utter disinterestedness: “He never said, I discovered this adaptation or invented that combination, but showed the whole thing as if the Divine artificer had made it, and he had happened to find it” (541; bk. 2, ch. 8). So far, so mid-Victorian in tone, but he is contrasted with the shallow proto-aesthete Henry Gowan, a sinister poseur constantly on the make, anticipating certain dubious icons of the 1880s and 1890s; it’s as if Dickens himself, unknowingly, was going beyond Dickens! Doyce offers a typically dry assessment of Gowan: “Why, he has sauntered into the Arts at a leisurely Pall-Mall pace […] and I doubt if they care to be taken quite so coolly” (224; bk. 1, ch. 17). This motif, of stern integrity and dedication set against the idle, rich, and undeserving, is repeated with variations in a cluster of post-Dickensian novels by those authors who were familiar with the Dickens canon. The present article is concerned with such novelists and their innovations on Dickensian motifs.

George Bernard Shaw: from “gentleman” to redefined “aristocrat”

Shaw claimed that Dickens “caught me young” and that “my works are all over Dickens” (Shaw on Dickens 102, 70). These quotations, taken together, establish both his old-fashioned affection for Dickens and a signal – for his own creative purposes – of his more radical agenda. He considered that Little Dorrit was “a more seditious book than Das Kapital” (Shaw on Dickens 51). Shaw’s first complete novel, Immaturity, written in 1879 but only published much later, has a minor character, Fraser Fenwick, a pathetic drunk who may owe something to the infantile-senile soak Mr. Dolls in Our Mutual Friend. That would be an obvious continuity, but more significant, in my view, is the apparent reincarnation of Daniel Doyce in the successful but snobbishly demeaned engineer Edward Conolly in Shaw’s next novel, The Irrational Knot (1880; 1905). The humbly born Conolly is in contention with the genteel parasites of London “society.” His confrontational discourse makes much of the definition of a “gentleman” as class-based or character-based in a manner that will recall Great Expectations. Conolly, however, has promotion for the character-based “gentleman” in prospect: he claims that he and his skilled peers “are the only genuine aristocrats at present in existence” (Shaw Irrational 205). Aristocrats: this is closer to, say, a French notion of the artist as aristocrat (if we take Conolly as the equivalent of an artist: he is a creator, after all). That language is distinctly un-Victorian and un-Dickensian, insofar as the “gentleman,” as character-defined, is based on an essentially conservative and middle-class consensus that an individualistic work ethic is the ultimate solution to society’s ills. The redefined “aristocrat” rejects such a pious (and philistine) notion in favour of a meritocracy fit for the new – and imminent – twentieth century.

Conolly must be distinguished from Doyce, who is still the solid entrepreneur with the self-help ethic so effectively espoused by Dickens himself in his own career. Doyce may be up against the state bureaucrats, but he is not challenging the social order. The more subversive aspirants of Shaw and, say, H.G. Wells go on to do just that. So even the most ardent of Dickens’s disciples are keen to revise his legacy.

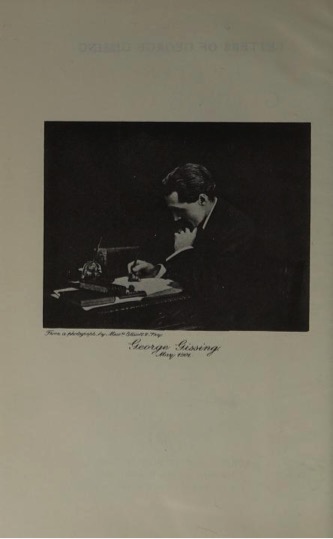

In his preface to The Irrational Knot, Shaw implicitly confesses to being a transitional figure between the Victorian and the modern; the final chapter of his novel, he writes, is “so remote from Scott and Dickens” and is rather “so close to Ibsen” though it “was written years before Ibsen came to my knowledge” (xxiv-xxv). The Doyce/Conolly archetype would also be in transition in a novel by Shaw’s junior by a year, George Gissing. Published in 1892, Born in Exile has as its main character a down-at-heels man of parts with a claim to the status of natural aristocrat: the lofty Godwin Peak, in his aspirations, is well named.

George Gissing: a committed Dickensian – with reservations

Gissing’s first novel, Workers in the Dawn (1880), is more in the traditionally Dickensian mode. It is the tale of a waif, Arthur Golding, who wanders the East End of London and is initially cared for by a baked-potato seller, Ned Quirk, who feeds him for free, and is then adopted by the kindly Brownlow-figure, Mr. Tollady, who teaches him his own trade of bookselling and printing. There is quite a cast of fairy godparents and not a few bad fairies. Dickens-style names abound: Whiffle, Blatherwick, Clinkscales, Pettindund, and the like. Critics have noted similarities with the plot of James’s Princess Casamassima: Gissing’s Golding and James’s indigent bookbinder both struggle with divided loyalties to art or to political commitment; that conflict is not so much a feature of the Dickens canon. However, both young men discover that they are more highly born than they or others had assumed: we can then claim James’s book as his most Dickensian-Gissingesque!

Gissing is still regarded as one of Dickens’s best critics, as evident in his monograph Charles Dickens (1898) and the essay collection The Immortal Dickens (posthumously published in 1925). However, his ample admiration had its limits: anticipating the twentieth century’s following for Dostoevsky, he noted that “Raskolnikoff himself [in Crime and Punishment], a man of brains maddened by hunger and by the sight of others hungry, is the kind of character Dickens never attempted to portray; his motives, his reasonings, could not be comprehended by an Englishman of the lower middle class” (Gissing Charles Dickens 223).

W.H. Hudson: mean streets and rural retreats

Gissing’s friend, W.H. Hudson, is not generally considered to be within Dickens’s orbit; he’s the writer best known for his South American romance, Green Mansions (1904). This Anglo-Argentinian, who was raised on the pampas, was taught by an expatriate, a Mr. Twigg, a talented actor who regaled his pupils with performances of Dickens’s works. Yet, for a long time thereafter, Hudson could not quite share his old teacher’s enthusiasm. Later, he became more ambivalent and at least was ready to be persuaded. Keenly anticipating his friend’s 1898 book on Dickens, Hudson displayed, in a letter to Gissing, an idiosyncratic take on one of the major figures in David Copperfield: “It struck me that Uriah [Heep] was one of the small minority of sane persons in the book” (Landscapes and Literati 31). A compliment with a sting?

Hudson’s novel Fan (1892) is an uncharacteristic work for him, not unlike a Dickens or a Gissing novel with its female protagonist’s early life in a London slum and her subsequent wanderings, her erratic rescue by Mary Starbrow, a temperamental but ultimately loyal haute-bourgeoise fairy godmother. Near the end of the novel, it is revealed that the sometime waif is of a more exalted parentage than her squalid upbringing would suggest; the parallels with Workers in the Dawn and, of course, with Oliver Twist are clear. Jason Wilson, author of a recent book on Hudson, regards the novel as “a Dickensian pastiche” (251-52) but is impressed enough to make valuable (and rare) comments on it.

Fan contains its version of the Doyce/Gowan antithesis. In rural Wiltshire, Fan befriends a thoughtful and personable artisan, the carpenter Cawood, and enjoys intelligent conversation with him. He’s a freethinker who respects those of faith and is a devoted family man. His integrity is contrasted with the ineffectual and deluded London literary dabbler, Merton Chance (well-named), whose wife can’t rely on him; one of his friends likens him to Mr. Mantalini, the pretentious, parasitical fop in Nicholas Nickleby (evidence that Hudson was more alert to the Dickens canon than we might assume). There may be a hint here of Hudson’s preference for rural over urban life. A naturalist and ornithologist, he remembered only too well how he found a haven in Hyde Park during his period of indigence when he first settled in London; such experience could have helped to make him more sympathetic to Dickens (Wilson 10).

The arts of William De Morgan: from pots to plots

A friend and sometime colleague of William Morris, William De Morgan is the celebrated ceramicist of the Arts and Crafts movement. Versatile in a range of visual forms, he was in his sixties when he embarked on a second career as a novelist. He set his books not in the Edwardian years of their publication, but in mid-Victorian times, and declared that “I owe to Dickens everything that a pupil can owe to a master – the head master” (De Morgan qtd. in Stirling 272). There’s a certain cosiness, jovially Pickwickian, to these anachronistic works, it would seem. However, his only essay on Dickens is devoted to Our Mutual Friend and to its darkest pages. He finds the master at his most intense and tragic in the scenes with Bradley Headstone, the frustrated, doomed schoolteacher (De Morgan “Dickens’s Best Story” 88, 89).

De Morgan’s most celebrated novel, Joseph Vance (1906), certainly possesses the more traditional Dickensian ticks, such as the portrayal of the unctuous Reverend Benaiah Capstick, who professes that as the existence and abundance of Divine Grace depends on sin, sinners should be encouraged to indulge themselves to the full. However, the Doyce/Gowan pattern also persists: Joseph Vance is a bright lad of promise from a limited working-class family who is taken up by a fairy godfather/guardian figure. He becomes a successful engineer and a beacon of decency, in contrast to the sinister Beppino, a third-rate poet with a phonily drawling mode of speech. A recent critic has pointed to Beppino’s closeness to the fluting-voiced aesthetes in George Du Maurier’s caricatures of the late 1870s and into the 1880s (Maltz 50-52). A decade after Dickens’s death, his old villains assumed new metamorphoses. As someone associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, De Morgan may well have encountered such grotesques among the consumers, rather than the producers, of works of art.

The Anglo-Jewish novelist Israel Zangwill was dubbed “the Dickens of the Ghetto” for his fiction based in the working-class milieux of London. He is best known for the sprawling novel Children of the Ghetto (1892), which has a young Jewish character, Benjy, who aspires to be a writer and claims, cockily enough, that he might well surpass his literary idol. Unlike Dickens, Benjy knows Latin and Greek, which he thinks will tip the scales in his favour; his death, however, is tragically untimely. The novel is a fictional witness to the growth, in the 1880s and 1890s, of working-class socialist movements in their specifically Jewish manifestations. This all goes well beyond Dickens’s bourgeois paternalism.

H.G. Wells and science

There’s a continuing sense of socio-political changes since 1870 to match the artistic innovations so prized by Henry James. Yet both proximity to and distance from Dickens are still to the fore, oscillating to and fro. In an amiably knock-about correspondence with Arnold Bennett, who cosmopolitanly championed Balzac, H.G. Wells declared himself for the home-grown Dickens and his “astonishing gargoyles” (Personal and Literary Friendship 47). The dingy draper’s shop in Wells’s Kipps (1905) is a counterpart to Dickens’s blacking factory, but the “Doycean” inventor George Ponderevo in Tono-Bungay (1909) is a very different scion of shabby gentility from the chirpily naïve Kipps. In 1927, E.M. Forster remarked that “perhaps the main difference between [Dickens and Wells] is the difference of opportunity offered to an obscure boy of genius a hundred years ago and forty years ago. The difference is in Wells’s favour. He is better educated than his predecessor; in particular, the addition of science has strengthened his mind and subdued his hysteria” (25). The more pessimistic strain in Wells is not, however, “subdued” in the portrayal of Ponderevo with his ominously prophetic deployment of scientific and technological advance – “And now I build destroyers!” (Tono-Bungay 483).

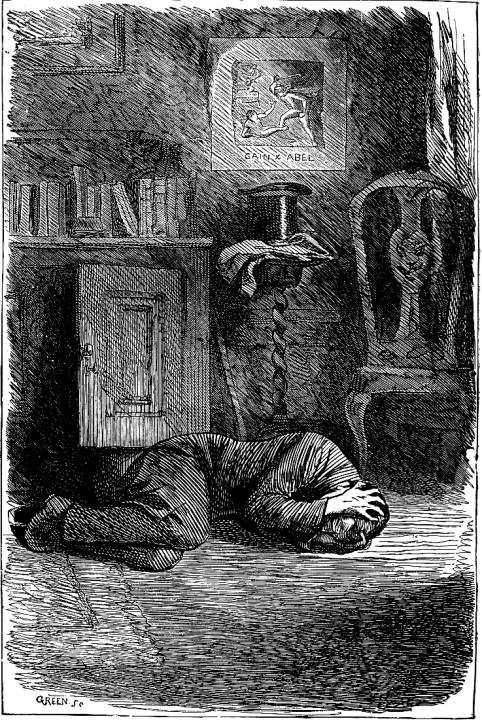

Robert Tressell: working-class integrity?

Our last post-Dickensian is Robert Tressell, born in the year of Dickens’s death, and the working-class author of The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists (1914; full text 1955). The novel’s main character, Frank Owen, is a painter and decorator and an evangelical socialist among conservative workmates. The book’s traditionally Dickensian echoes are clear in such names as the town Mugsborough and characters such as Sweater, the Brigands, Crass, and Slyme. However, this is at last a book by and for the working class and reflects an Edwardian political-social climate unknown to Dickens. Like De Morgan, Tressell was an artist-craftsman, a mural painter to trade as De Morgan was a ceramicist; both drew on oriental or otherwise lavishly colourful motifs. Tressell’s Owen, in the novel, is involved in the design of a “Moorish Room,” and a surviving work by his author reflects, to some extent, an equivalent opulence. Surviving: Tressell’s work hardly fared as well as De Morgan’s. Tressell is broadly in line with both the artistic and political legacy of William Morris. De Morgan, more comfortably middle-class, was associated with Morris artistically but had no interest in his politics or, for that matter, in the socially reforming agendas of Dickens.

In the novel, Frank Owen is presented as a man who takes pride in his skill as applied to what is generally considered a lowly task. He imagines, in great detail, the ideal design for the Moorish Room: “The question, what personal advantage would he gain never once occurred to Owen. He simply wanted to do the work, and he was so fully occupied with thinking and planning how it was to be done that the question of profit was crowded out” (Tressell 122). We don’t know if Tressell’s reading of Dickens included Little Dorrit, but there is surely something here of the disinterested nobility of the neglected Daniel Doyce and his “dismissal of himself” in his labours (Dickens 541). As the destructiveness of 1914 approached, Tressell’s novel appeared that year only in truncated form. Dickens’s long reach – whether continued or modified by his successors – testified to the long reach of the creative spirit itself.

Works Cited

De Morgan, William. “Dickens’s Best Story.” Charles Dickens: A Bookman Extra Number. 1914, pp. 84-89.

–. Joseph Vance. London: Heinemann, 1906.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Revised edition. London: Penguin, 2003.

–. Our Mutual Friend. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008.

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1962.

Gissing, George. Born in Exile. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1892.

–. Charles Dickens: A Critical Study. London: Blackie, 1898.

–. Workers in the Dawn. London: Remington, 1880.

Hudson, W.H. Fan: The Story of a Young Girl’s Life. London: Dent, 1923.

–. Landscapes and Literati: Unpublished Letters of W.H. Hudson and George Gissing. Salisbury: Michael Russell, 1985.

James, Henry. The Princess Casamassima. London: The Bodley Head, 1972.

–. Selected Literary Criticism. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968, pp. 31-35.

Maltz, Diana. “Aesthetic Caricature in William De Morgan’s Joseph Vance.” Evelyn & William De Morgan: A Marriage of Arts & Crafts, edited by Margaret S. Frederick. New Haven: Yale, 2022, pp. 45-53.

Shaw, Bernard. Immaturity. London: Constable, 1930.

–. The Irrational Knot. London: Constable, 1905.

–. Shaw on Dickens. New York: Ungar, 1984.

Stirling, A.M.W. William De Morgan and His Wife. London: Thornton Butterworth, 1922.

Tressell, Robert. The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. Frogmore: Panther, 1965.

Wells, H.G. Arnold Bennett and H.G. Wells: A Record of a Personal and a Literary Friendship. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1960.

–. Tono-Bungay. London: Macmillan, 1909,

Wilson, Jason. Living in the Sound of the Wind: A Personal Quest for W.H. Hudson, Naturalist and Writer. London: Constable, 2015.

Zangwill, Israel. Children of the Ghetto. London: Heinemann, 1892.