Help us solve the savage stenographic mystery of “The Two Brothers”

Hugo Bowles and Daniele Metilli

Hugo is an applied linguist and associate professor of English at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, and has been researching and writing about Dickens’s shorthand for the last three years. His book Dickens and the Stenographic Mind will be published this year with Oxford University Press. Daniele is a computer engineer and digital humanist, currently doing his PhD in Computer Science at the University of Pisa. They are both cryptography enthusiasts and are working together on a crowdsourced online project called “The Dickens Code” which is aimed at collecting, digitising and deciphering all items of Dickens’s shorthand. Hugo will be talking about this in Tübingen on the first morning of the conference.

(shorthand images by courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Manuscripts Department)

When Dickens described the shorthand system that David Copperfield learned as a “savage stenographic mystery” (ch. 43), he wasn’t joking. Gurney’s Brachygraphy, with its “despotic characters” and symbols that looked like a “pen-and-ink sky-rocket” and “the beginning of a cobweb” (ch. 38) is indeed diabolically difficult to read. By a curious irony, Dickens has also left us with his own version of the stenographic mystery and we need your help to solve it. So here’s the puzzle.

Dickens was an occasional teacher of Gurney shorthand. Among his pupils were Catherine Hogarth’s brother Robert, his own sons Charles and Henry, and Arthur Stone, the son of his neighbour and friend Frank Stone. Dickens’s shorthand notebook, now at the John Rylands Library in Manchester, shows him to be an intelligent and thoughtful teacher. He realised that having to memorise a symbol standing for a word like “bankruptcy” was a waste of time so he got rid of the more irrelevant arbitrary characters and replaced them with new ones standing for frequently used words. He also altered some of the existing symbols so that they could stand for two or more letters at a time and even invented new symbols whose meaning was connected to their shape. It was really Brachygraphy 2.0.

Even though Dickens made sure that the symbols were less “despotic” for his pupils than they had been for him, they are still very hard to read because Brachygraphy is an alphabetical system that tends to reduce most words to a consonant skeleton, rather like a text message. We cannot read whole words off the page, just clumps of consonants that have to be turned into words, so symbols first have to be identified correctly and then the word has to be reconstructed. As David Copperfield found, this is an almost impossible task, particularly when a symbol like a dot can stand for four or five different words at a time.

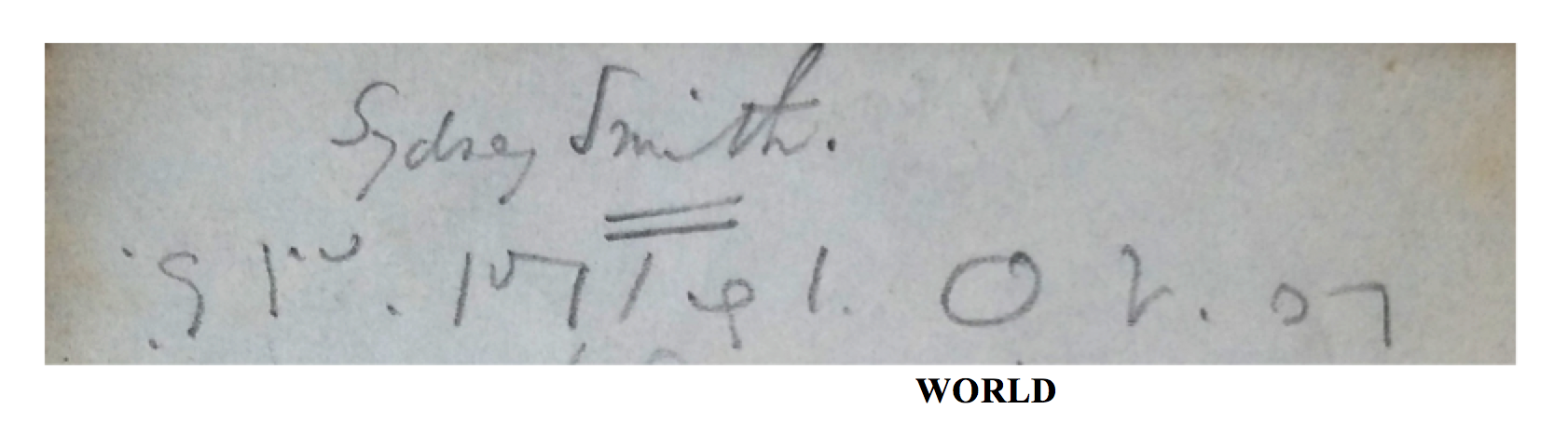

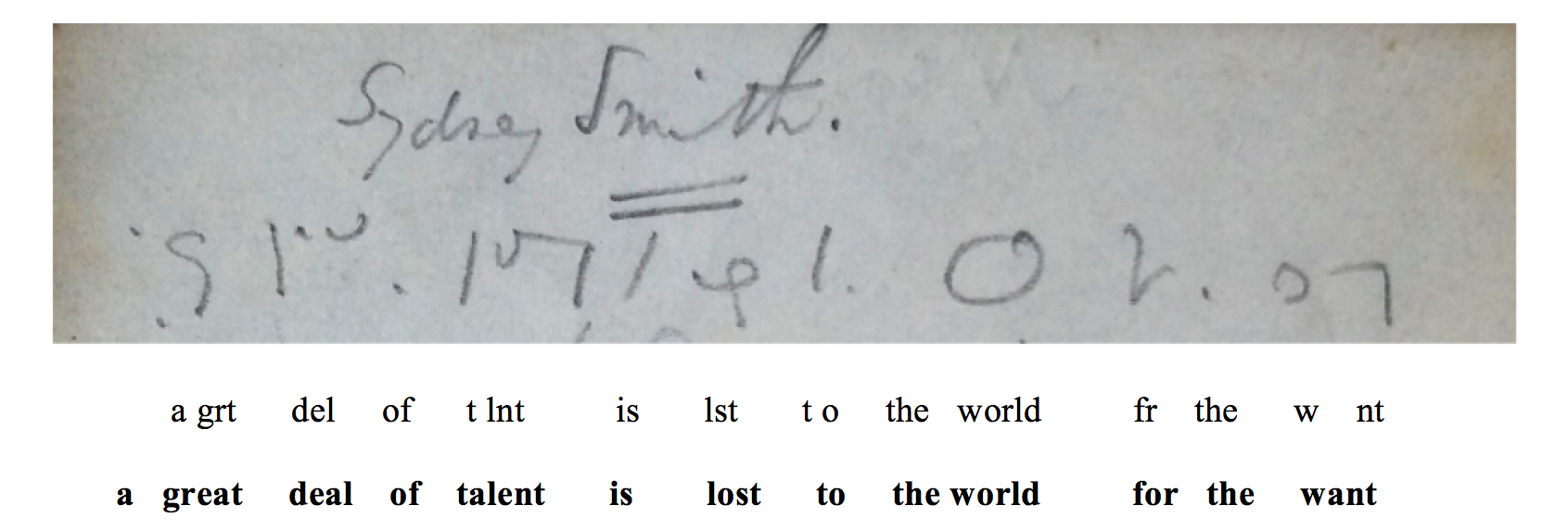

But there is hope. Arthur Stone left behind five teaching booklets, now in the archives of the Free Library of Philadelphia. These contain ten shorthand texts, five written by Arthur and five by Dickens, with their titles written in longhand: “Sydney Smith”, “The Two Brothers”, “Nelson”, “Anecdote”, and “Didactic”. These are clearly dictation exercises. Like Traddles, Dickens would have dictated the original text and he and Arthur would have written their versions of it in shorthand and compared notes. Here below is the first line of the Sydney Smith text, which is the only one to have been identified and transcribed so far (see https://doi.org/10.1093/notesj/gjx170).

All five dictation texts in Arthur’s booklets look more or less like this. There is a title in longhand followed by about 40 lines of shorthand covering two pages. So how do we find out what the shorthand says?

One way is to find the source material that Dickens was dictating from, or at least restrict the number of possible sources. Dickens’s lessons with Arthur took place at the offices of All the Year Round, so he might have used some material from AYR or picked a book off a shelf in the office or simply brought a book from home. In the case of Sydney Smith, Dickens was known to carry Smith’s work around with him, so that restricted the range of sources to his better-known works.

The Brachygraphy manual was then used to try to identify a few of the words in the text. Luckily, the first line of “Sydney Smith” contains a large circular symbol, which is an arbitrary character standing for “world”, so one needed only to look at the verbal context of all the instances of “world” in Sydney Smith’s work to see if it matched the other, more difficult symbols in the first line. There was a line from Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy, which seemed to fit:

Looking at the two version of the transcription, you can see how difficult it is to decode the shorthand off the page. It is not just a question of decoding the symbols correctly. If you decode two symbols as the consonant cluster “fr”, for example, it might expand into “fur”, “far”, “for”; “fair”, “fare”, “four” and so on. The range of possible words in any sentence is extremely high and this makes it very hard to be sure when a word has been correctly decoded.

The challenge is to do the same with “The Two Brothers”. Does anyone out there have any ideas about what the source might be just from looking at the title? Can anyone decode the text or parts of the text? Here below is the first page of the shorthand text of “The Two Brothers”, with the title just visible at the top of the page. We have made a tentative start at decoding and written some of the words in blue underneath the shorthand but we are not 100% sure that they are correct.

Why not have a go yourselves? You can get started by downloading the Brachygraphy manual here. If it’s any consolation, you will be navigating your way through the same “sea of perplexity” (ch. 38) that terrorized David Copperfield. So enjoy the sailing and do send your comments and suggestions to us: bowleshugo[at]gmail.com ; daniele.metilli[at]gmail.com.

Join us for our ‘Dickens and Language’ symposium, taking place this year in Tübingen, to hear more about this research. Find out more, and view the schedule, here.

Hi, I´m Fernando from ARgentina.

Unfortunately, the book is no longer available. I found this one that maybe can help me decipher some other stenograms. Could you tell me if I’m on the right track even with this old version?

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=7VdgAAAAcAAJ&pg=GBS.PA2&hl=es_419

HOpe you can read this message!

Hi Fernando. Apologies for the late reply to your question. I have reached out to Hugo Bowles to ask if the book you have listed above would work for further transcriptions and I will reply back when I hear from him. I’m not sure if you are following the work the Decoding Dickens Team is doing. Their website has several resources for those who would like to take part: https://dickenscode.org/resources/. Hopefully you will find those to be helpful!

Fascinating. But:

“Here below is the first line of the Sydney Smith text, which is the only one to have been identified and transcribed so far (see https://doi.org/10.1093/notesj/gjx170).”

This links to a Notes & Queries article which isn’t Open Access, so all that we non-academic folk without institutional subscriptions can read, is the abstract. Not hugely welcoming to the prospective crowdbrain volunteer …

Hi Tim. I have reached out to Hugo Bowles to ask if there is a way that we can read his work in “Notes & Queries” on an open access platforms. Many scholars have PDF documents of their work which they are happy to share and I will certainly post back when I hear from him. It may be of interest to you that the team have completed more work on “The Two Brothers”: https://dickenscode.org/you-have-seen-me-before-tonight-transcribing-the-two-brothers-part-ii/