The Tell-Tale Sign of the Dickensian Influence: Dickens and Poe

Katie Bell holds a PhD in English from the University of Leicester. She can be found on Twitter https://twitter.com/decadentdickens and on https://www.notions-nineteenth.com/

Dickens’s works are most associated with hearth and home, goodwill to one’s neighbors and the value of conviviality. His more macabre storylines are sometimes left to the dark corners in which they are best read, but as Halloween is upon us, let us explore one of his lesser-known gruesome tales: “A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second.” The godfather of horror stories, Edgar Allan Poe, was very taken by Dickens’s tale, and as will be explored here, it had a great influence upon one of his most ghastly stories: “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

From 1835 until his death in 1849, Poe wrote approximately one thousand critical pieces and set the standard in America for book reviewing. When he reviewed Sketches by Boz in June of 1836, Poe identified himself as one of the first fans of Boz. Poe had never heard of Dickens (or Boz) prior to his review (Sketches was Dickens’s first collection, so few readers in America knew of him), and Poe wrote of Dickens: “we know nothing more than that he is a far more pungent, more witty, and better disciplined writer of sly articles, than nine-tenths of the Magazine writers in Great Britain” (Poe “Critical Notices” 447). In 1841, two years before he wrote “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the short story for which he is best remembered today, Poe reviewed Dickens’s Master Humphrey’s Clock in Graham’s Magazine. He specified that of all the tales held within it, “A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second” was the most “power[ful]” (Poe “Review of New Books” 249). He wrote,

The other stories are brief…The narrative of ‘The Bowyer,’ as well as of ‘John Podgers,’ is not altogether worthy of Mr. Dickens. They were probably sent to press to supply a demand for copy…But the ‘Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second’ is a paper of remarkable power, truly original in conception, and worked out with great ability (249).

In 1843, when “The Tell-Tale Heart” was published in The Pioneer, it was extremely well received by both its American and its British readers. The success of the tale is due in part to the extent to which Poe utilized the then-undefined Freudian term “uncanny,” but also to the powers of Poe’s editorial skills: his talents at seeing how best to manipulate a rough plot into a crafted tale.[1] “The Tell-Tale Heart” owes an enormous debt to Dickens’s early work with “Confession,” but it is not merely a regurgitation of Dickens’s works. Poe crafted a finely tuned tale of psychosis from the seed of the idea began by Dickens.

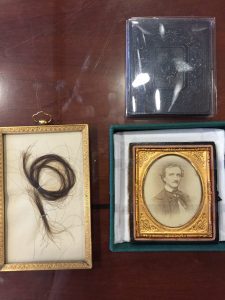

Hair and daguerreotype of Edgar Allan Poe courtesy of the Enoch Pratt Library, Baltimore MD. Photo by the author.

Dickens’s “Confession” centers on a retired soldier in the late seventeenth century who adopts his nephew only to be haunted by the boy’s gaze. This fixation causes the narrator to begin his slow descent into madness as he plots the boy’s murder. In “Confession,” Dickens glosses over the actual murder, and instead the soldier wakes up to find the boy already dead. Dickens chooses to focus on the psychological undoing of the soldier while he is planning to bury the boy in a part of the garden which had been newly planted. He subsequently falls into an obsession with the plot of ground, watching it every day for signs of change. It is here that the reader will begin to notice an uncanny (to borrow the term from Freud) similarity to “The Tell-Tale Heart.” On the fourth day after the murder, an old friend comes to call upon the soldier, bringing with him a second, unknown visitor. The narrator entertains his two guests with refreshments outside and, in a pompous fashion, places the table and chairs upon the very spot where the boy is buried, exactly as in Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” At first, the murderer is assured that his secret is safe. However, the visit lingers on and errant bloodhounds, having escaped from their master nearby, invade the party. They announce themselves with “a low deep howl” (Dickens 46; 2). The bloodhounds slowly begin circling the party, having sniffed out the boy’s remains, and the soldier gives his deed away by refusing to move from his spot over the grave. The second, unknown soldier guesses that there is a ‘”foul mystery”’ there and the two detain the narrator while the “angry dogs t[ore] at the earth and thr[ew] it up into the air like water” (Dickens 47; 2).

Poe’s narrator gives up his crime in a similar fashion. He is haunted by the sound of his victim’s heartbeat under the floor, and he believes that others can also hear the sound but are ignoring it in order to make “a mockery of [his] horror” (Poe “Heart” 265). Poe’s story ends famously with the narrator shrieking his guilt to the officers: “tear up the planks! here, here!–It is the beating of his hideous heart!” (Poe “Heart” 265). In the first version, penned by Dickens, once the murderer is faced with his victim’s remains, he confesses his guilt to his two guests, is tried and sentenced to death. From comparing these two stories, it can be seen that Poe crafted a more succinct version that focuses on the psychosis of social outsider. This unnamed man becomes so consumed by his fear of oppression or undoing (via the gaze of “the evil eye”), that he turns to murder in order to free himself from his perceived oppressor (“the evil eye” itself) (Freud 147).

Unquestionably, “A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second” published in 1841 had a hand in shaping “The Tell-Tale Heart” of 1843. “Tomahawk Poe” (the nickname by which his contemporaries came to call him) streamlined Dickens’s piece into a tale examining the psychology of the killer, as well as the act of the murder. A mania drawing one to murder is an idea which Dickens made an effort to touch upon in “Confession,” but for reasons unknown (perhaps his being in the early days of his authorial career), were either glossed over or not teased out as thoroughly as they could have been. As well, Dickens focused too acutely on the history of his narrator and his relationship to the young boy at the exclusion of the important psychology behind the murder: the power of “the evil eye.” Poe kept the aspects he so loved in “Confession,” such as the first-person narration of the killer himself, the oppressive power of eyes, and the final feast over the hidden burial, but fashioned something which read more cleanly, with less backstory weighing down the plot. Instinctively always an editor, Poe recognized Dickens’s work as being “truly original” but cut out the parts he felt were extraneous (Poe “Review of New Books” 249). In Poe’s version, the relationship between the murderer and his victim was not important; instead, what was crucial was the perceived oppression (as Freud would later surmise, oppression is projected envy) which “the evil eye” held over the murderer. Poe was undoubtedly “paying homage” to Dickens, but he did so in a way that gives a rebirth to Dickens’s work (Galván 16).

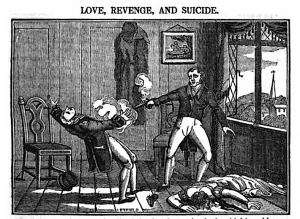

Wood engraving by John Byfield for The Terrific Register, 1 January 1825 via Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Of course, the influence of the publication of “penny dreadfuls” and “penny bloods” on Poe and Dickens alike should not be underestimated, for influential they were.[2] However, the penny publications focused most acutely on the shock value of the act of horror and not necessarily on the finer nuances of the criminal, or damaged mind. Poe’s tales brought something new to the genre, something beyond the mere shock factor. Due to his exploration of the sense of loss, isolation and the longing for community within his texts, Poe addressed themes with which the modern Victorian (American and British alike) was struggling. The changes that came in the middle of the nineteenth century to Britain and America created a vacuum within which the Victorian man/woman sought to create and stabilize his/her identity; ideas of psychology, the outsider, and those who are deemed to be “other” abound in literature of the nineteenth century. It is when Poe first became aware of Dickens in 1836 that we can see Poe’s works begin to delve more into exploration of the psychological underpinnings of the minds of everyday Victorians. Poe’s exposure to Dickens sparked in him an interest for the American author in psychology, an interest he continued to explore throughout his literary career. Although Poe was appreciated during his life, he never reached the recognition while alive that he sought. Reading these two versions of the same tale together reveals chains of causality between American and British literary audiences, and demonstrates that a common bond united these two canonical writers: the desire to explore the outsider in our society, who is searching for where he belongs.

[1] Freud writes, “the ‘uncanny’ is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar” (Freud 124).

[2] Dickens wrote that he was captivated by a magazine called The Terrific Register. He explained to his friend (and later biographer) John Forster that the stories made him “‘unspeakably miserable, and frighten[ed the] very wits out of [his] head, for the small charge of a penny weekly; which, considering that there was an illustration to every number in which there was always a pool of blood, and at least one body, was cheap’” (Forster vi). For more about The Terrific Register, see the British Library.

We are not privy to much of what Poe read for “fun” during his teenage years. He did live in and around the London area from 1815-1820, and we can only surmise what fascinating magazines he may have turned up on a free afternoon.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. “A Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second.” Master Humphrey’s Clock and A Child’s History of England, Oxford University Press, 1958, pp. 41-48.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens, Vol. 1. Osgood and Company, 1875.

Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny.” The Uncanny, translated by David McLintock, Penguin Books, 2003, pp. 121-162.

Galván, Fernando. “Plagiarism in Poe: Revisiting the Poe-Dickens Relationship.” The Edgar Allan Poe Review, Vol. 10, no. 2, 2009. pp 11-24.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “Critical Notices.” Southern Literary Messenger, Vol. II, no. 5, June 1836, pp. 445-460.

–. “The Tell-Tale Heart.” The Annotated Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2015, pp 259-265.

–. “Review of New Books.” Review of The Old Curiosity Shop and other Tales and Master Humphrey’s Clock by Charles Dickens. Graham’s Magazine, May 1841, pp. 248-251.

THANK YOU, Kathie,

can I translate THIS ARTICLE into Hebrew [giving you the credit] for my blog? NON COMMERCIAL USE

THANKS

A.Goldberg

Hi Avi. Thank you for reaching out to ask for permission, and yes, that would be fine. If you would, please link our original post once you are ready to put the translated version up on your blog.