Dickens’s Desk-World of “little familiar objects”

This post was contributed by Pratibha Rai, an interdisciplinary graduate from the University of Oxford. Her research area is in the visual world of literature and the ways in which authors apply material objects, illustration, and their own aesthetic sensibilities to shape meaning in narratives. She has written on Jane Austen’s dialogue with the visual theory of ‘the picturesque’ and Van Gogh’s lifelong passion for Charles Dickens’s illustrated works. Pratibha can be reached on Twitter @TibhaWrites

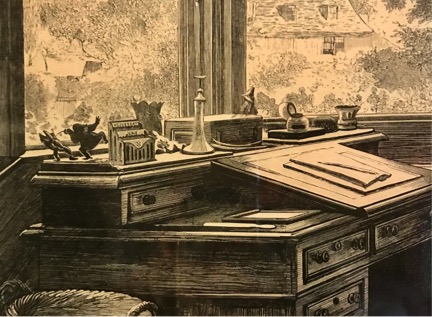

Luke Fildes’ haunting engraving The Empty Chair (1870) honours Charles Dickens’s desk and evokes the sorrow of the author’s sudden death through the melancholy medium of still life. The perspective creates the sense that we have just entered a freshly abandoned study, the chair angled as though anticipating its owner’s return. For me, the most eye-catching feature of the engraving has always been the miscellany of miniature objects on his writing desk; an area of his study that can often be missed in the shadow of heavier items. Fildes himself was struck by these trinkets when he was invited to Kent after the Westminster funeral in belated fulfillment of the author’s wish and was taken aback by the unusual assortment of cherished objects on Dickens’s desk.

Perhaps in response to his lively interest and wanting to encourage the young artist whose career might have been adversely affected by the termination of Drood, Dickens’s sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth gave him a quill pen, memorandum slate, and a piece of blue stationery from the collection to keep. Georgina was bequeathed the desk objects in Dickens’s Will, handing to her, “my personal jewellery…and all the little familiar objects from my writing-table and my room, and she will know what to do with those things” (Charles Dickens’s Last Will and Codicil, 12 May 1869 and 2 June 1970). It is unclear whether Georgina knew what to do with the “little familiar objects” because she was instructed in advance or was trusted to act on her own initiative, knowing their personal value to the author. Nonetheless, we know that she preserved them and a selection of his desk-world of familiar objects is kept in the Charles Dickens Museum, London.

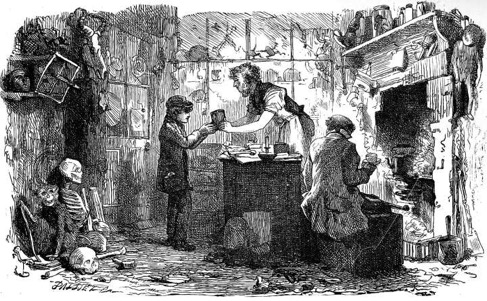

Alan Watts describes the humorous knick-knacks that decorated the author’s writing space in his book Dickens at Gad’s Hill: “On top of the desk were various objects Dickens enjoyed having in front of him when he was writing – the two fat toads fencing, the little monkey wearing a pill-box cap, the statuette of a dog-fancier with little dogs under his arms and peeping out of his pockets, the gilt leaf on which a rabbit was sitting…”(36-37). The “two fat toads fencing” immediately recalls an episode in Chapter VII of Our Mutual Friend, when Silas Wegg walks through Clerkenwell and stops at Mr. Venus’s taxidermy shop. As Wegg peers through the dark window, he observes “a muddle of objects vaguely resembling pieces of leather and dry stick, but among which nothing is resolvable into anything distinct, save…two preserved frogs fighting a small-sword duel.” There is evidence to suggest that the preserved frogs were indeed modeled on the duelling toads on Dickens’s writing desk. In Fildes’s The Empty Chair, we can see Dickens’s fighting toads at the left-hand side of the desk in a pose that strikingly resembles the fighting frogs in Marcus Stone’s accompanying illustration to Chapter VII, “Mr. Venus surrounded by the Trophies of his Art.”

Dickens’s friend and eminent literary critic, John Forster states that Marcus Stone discovered the original Mr. Venus’s shop in St Giles and took Dickens to visit it (Dean 22). The author might then have introduced the idea of the dueling frogs into the novel after the figures on his desk, leading Stone to use the figures in his illustration of the comic-grotesque shop. Through this collaboration, it is notable that Dickens’s desk objects were not solely curiosities for his private amusement but added texture to the literary world which he invites his audience to enter in both text and illustration.

John Forster adds in his biography of Dickens that the fencing toads were a French bronze group and the statuette of the dog-fancier was also a French bronze figure full of comic suggestion, “such a one as you used to see on the bridges or quays of Paris, with a profusion of little dogs stuck under his arms and into his pockets” (212). Continuing with the French theme, the Dickens Museum also showcases a 1840s French ceramic jug with a blue glaze and decorative olives that can be traced back to Les Baines in Eastern France and thus, was likely bought as a souvenir during one of his many trips to France. Through this quaint object, one can imagine the author being transported to souvenirs of his travels, revealing his enjoyment of surrounding himself with items from his adventures and reinforcing his unique affection for small objects. Forster also mentions that his desk had a “little fresh cup ornamented with the leaves and blossoms of the cowslip, in which a few fresh flowers were always placed every morning – for Dickens invariably worked with flowers on his writing-table” (212). It is notable that this object, similar to Dickens’s own description of his desk ornaments, is characterised as “little” – diminutive objects in particular occupied a privileged and permanent place on his writing desk.

The value of little objects is striking when juxtaposed with, what Dickens calls in Our Mutual Friend, the “Hideous solidity” of Victorian material culture where, “[e]verything was made to look as heavy as it could, and to take up as much room as possible” (Ch. 11, Book 1). Against this imposing solidity, diminutive objects were vulnerable to mockery as we see in The Mystery of Edwin Drood when the heroine of the novel, Rosa, runs away to London and packs “a few quite useless articles into a very little bag” (Ch. 20). The bag’s smallness amuses Mr Grewgious who asks, “’Is that a bag?…and is it your property, my dear?’” (Ch. 20). The patronising tone conveys how the diminutive could be dismissed as insignificant and be the subject of comic treatment. Dickens however did not snub smallness; he highly prized little objects and they held his imagination during the course of writing, as Forster relays, “Ranged in front of, and round about him, were always a variety of objects for his eye to rest on in the intervals of actual writing, and any one of which he would have instantly missed had it been removed” (185). It is clear that he was attached to these decorative objects as they mysteriously aided his writing process but also in a sentimental fashion, “missed” them as though they were individuals.

In this way, they are reminiscent of the sentimental “personal property” that appears in his works. In Great Expectations, Wemmick collects curiosities and accepts any object from his clients, regardless of how absurd or trifling they might be, on the grounds that “’they’re property and portable’” and he encourages Pip to “’Get hold of portable property’” (Ch. 24). This is financial advice for young Pip as “portable” objects can be readily exchanged for cash. However, the value of these small objects such as his collection of mourning rings and brooches is not solely monetary, they are material mementos of his departed clients’ untold histories; reliquaries that have an enduring value because of their link to individual histories. By possessing these gifts, Wemmick is “quite laden with remembrances of departed friends” (Ch. 22) and thus, these small objects are entangled with his social connections.

The fact that small objects were enmeshed with social relations is exploited to comic effect in Nicholas Nickleby when Miss Ledrook arrives at a wedding wearing, “the miniature of some field-officer unknown, which she had purchased, a great bargain, not very long before” (Ch. 25). Through the performance of intimacy by possessing “portable property” in the Great Expectations sense, Miss Ledrook can amusingly lay claim to a liaison with a dashing field-officer while knowing nothing of the historic gentleman represented. The entanglement of small objects with Dickens’s own social relations is visibly seen on his desk. His eldest daughter Mamie recalls how, “On the shelf of his writing table were many dainty and useful ornaments, gifts from his friends or members of his family” (My Father as I Recall Him, 1896). One such “dainty and useful” gift that he kept on his desk was a Wedgwood pottery match container gifted to him at Brighton in gratitude for handling his landlord’s mental collapse. In the eventful episode ca.1850, Dickens was staying in rented accommodation when he and his group were driven out owing to the landlord and his daughter being removed and taken to a psychiatric institution by doctors. The match holder present must have been valuable to him as it features in Fildes’s The Empty Chair, showing how he kept it on his desk until his death.

© Charles Dickens Museum, London

Pondering the fate of his desk ornaments when he wrote his will, Dickens might have been acutely aware of the immense vulnerability of portable property. In David Copperfield, Traddles shows David the household items he has stored up for his future married life with Sophy: “’two pieces of furniture to commence with. This flower-pot and stand, she bought herself. You put that in a parlor window,’ said Traddles, falling a little back from it to survey it with the greater admiration, ‘with a plant in it, and—and there you are! This little round table with the marble top (it’s two feet ten in circumference), I bought’” (Ch. 27). Traddles speaks gleefully of these “little” objects and it is clear that their significance lies not in their economic value but in their representation of the couples’ mutual commitment as they have each bought an item from their means in their hopes of living together. However, the flowerpot and small marble-top table are almost disastrously lost after Traddles acts as Mr. Micawber’s guarantor. No doubt that losing these objects would be akin to losing treasures. Traddles and Sophy are able to finally marry toward the close of the novel and the table and flowerpot indeed furnish their rooms. These objects therefore tell a narrative of the hope, patience, and dedication required to secure a comfortable future – thus, it is the stories and people attached to the items that allow the Traddles’ apartment to feel like home.

In a similar way, Dickens’s desk-world of ornaments was integral to creating an atmosphere of home. Though these small objects were vulnerable to being dismissed amid the heaviness of Victorian material culture, they held a profound importance for Dickens – they were portable and travelled with him, set the stage for his writing, and were not only “quite laden with remembrances” (Great Expectations, Ch. 22) of his social relations but also uniquely functioned as companions themselves in Dickens’s lived experience.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens, New York, 1990.

Charles Dickens’s Last Will and Codicil, 12 May 1869 and 2 June 1970.

Dean, F R. THE FIGHTING FROGS, Dickensian; London Vol. 45, January 1, 1949: 22.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield, United Kingdom, Collector’s Library, 2004.

… Great Expectations, Penguin Classics, 1985.

…Nicholas Nickleby. United States, Cosimo Classics, 2009.

…Our Mutual Friend, United Kingdom, Chapman & Hall, Limited, 1892.

…The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Penguin Classics, 2002.

Dickens, Mamie. My Father as I Recall Him, Project Gutenberg, 1896, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/27234/27234-h/27234-h.htm.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens, Germany, Tauchnitz, 1874.

Watts, Alan. Dickens at Gad’s Hill, Elvendon Press, Berkshire, 1989.

Thank you for this Pratibha – I really enjoyed reading it! Fascinating connections – and I love the thought that Georgiana would instinctively know how to treasure these objects as they deserved.

Grewgious’s name – incidentally – reminds me of gewgaws; perhaps a little joke about his looking down on little things?

Also, re: Miss Ledrook’s brooch, do you know the Gilbert and Sullivan version of this joke – made forty years later in Pirates of Penzance (1879)? It is a favourite of mine!

General: I come here to humble myself before the tombs of my ancestors, and to implore their pardon for having brought dishonour on the family escutcheon.

FRED. But you forget, sir, you only bought the property a year ago, and the stucco on your baronial castle is scarcely dry.

GEN. Frederic, in this chapel are ancestors: you cannot deny that. With the estate, I bought the chapel and its contents. I don’t know whose ancestors they were, but I know whose ancestors they are, and I shudder to think that their descendant by purchase (if I may so describe myself) should have brought disgrace upon what, I have no doubt, was an unstained escutcheon.

I’m very glad you enjoyed the post, Beatrice!

Thank you for that brilliant bit of cratylic naming – I completely agree with you about Grewgious/Gewgaws! My favourite of Dickens’s cratylic names must b Mr Pickwick; reminiscent of a tallow candle with a drooping wick that needs to be constantly picked to stay alight. Despite Pickwick being tangled in misadventures, he continues to keep his light shining.

I am also grateful for the satisfying Pirates of Penzance joke! I love the phrase “descendant by purchase”. The sense of family belonging that small heirlooms bring can be powerful. In Pierre Bourdieu’s seminal work, ‘Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste’ (1984), he sees family heirlooms as “material witness” to the continuity of lineage; they consecrate a social identity which has proven permanence over time. The heirlooms in effect, transfer the virtues, values, and competences, which represent a particular family. I suspect this is the reason why I feel so moved when Micawber is arrested and his wife Emma is forced to pawn all of her family’s heirlooms!

I am so glad to read such articles about the fencing frogs standing on Dickens’ desk.I also wonder the origin of this frog statue. After reviewing Dickens’s letters, I found that this frog sculpture was likely a gift from a British businessman named Thomas C. Curry during his trip to Italy. In a letter dated October 17, 1844, Dickens wrote: “I must thank you for the gift you sent me. It is currently on my desk, and I hope it will remain here for many years.” However, since the letter versions are not complete, I haven’t found the full correspondence between them. If you could continue to explore based on this letter, I think the results would be very interesting. I will share my email address plz share me your latest findings!