The Tale of a Jug

This post is contributed by David Clement Davies, an author, sculptor, and visual artist. As a writer, he has won the Family Award and 76 Selections in the US. His website is dcdsculpture.com, where you can contact him directly about sales or commissions. If you are ever interested in visiting Pietrasanta and sharing some of these techniques and processes, please visit Sculptyourway.com. To visit Massimo Gentile’s wonderful resource, shop, and ceramic studio – Francesconi Ceramiche tel 0039 0584 790659 Alley of the Artisans, Via Umbria, 20, Pietrasanta, Italy. Copyright David Clement Davies 2024. All rights written and sculpted are strictly reserved. Photos Copyright DCD and Public Domain.

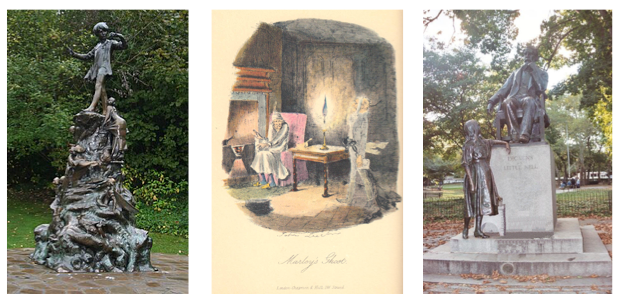

As a Fantasy author, but these days visual Artist too, it was still a little nervy dreaming of retelling Dickens’s A Christmas Carol–in clay. In a series of sculpted ceramic wine jugs, many with literary appeal, the running question was whether storytelling could transfer to such a different medium. Maybe the art to compare it with most would be the illustrator’s. However, as a Londoner myself, there is certainly a wonderfully evocative sculpture of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, but also of Dickens and Little Nell in Philadelphia. A vaulting masterpiece off the page replayed in so many adaptations, Carol has always haunted me, especially seasonally, of course, with its socially compassionate message too, reflected in Dickens’s readings and journeys from Britain and across America.

In our times of cultural wars and relativities, cancelling culture or pulling down past heroes and statues, for an artist wanting to draw both on History and Literature, Carol especially appeals because its message transcends a specifically Christian or certainly Christmasy one and becomes Universal in its rather simple journey from disillusionment and isolation, back to reconnection, celebration, and love. This is why Dickens underlines the nature of fiction and storytelling, too, in stressing that for the journey to work its magic, we must believe Marley is dead from the start.

In terms of appropriateness of joining mediums, though, I think all the Arts are essentially interconnected, so first, before technical skill or realization, comes drinking from the well of creative ideas. Then comes the shared Artistic obsession deeply embedded in Carol, namely what you leave behind. After moving from London to Italy in late 2017 with my wonderful rescue dog Rascal to an international sculpting centre like Pietrasanta in Tuscany, I was re-making my own future, too, by renewing an old love from school, perhaps like Scrooge’s lost Belle. Now, landing in a place carrying a huge creative tradition, replete with foundries, artists’ workshops and studios, marble quarries, and stone yards.

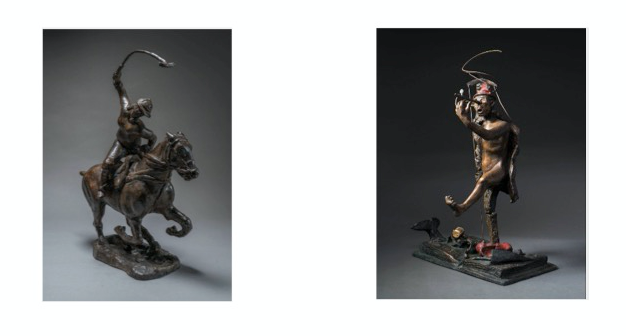

Perhaps as a storyteller seeking forceful meanings and expressions over aesthetics, I always loved figurative sculpture and working in clay: that ever magical, liberating material. “Clay is the life,” declared Antonio Canvoa (1757-1822), even if many rugged marble sculptors can dismiss the art as mere “modelling.”1 In loving movement, too, the first work I turned to was a horse and lady polo player–but with that writing brain still working in me, I turned to a series of sculpted fairy tales in bronze. These were very adult and rather grotesque works because, to me, great fairy tales always carry a sublimated darkness in fate, threat, magic, or sexuality. Yet by looking at the dark, too, through art, you emphasize and hopefully release the light. My aim is not to tell an entire story but to capture key elements and the spirit of tales like Little Red Riding Hood, more in the vein of Angela Carter or Rumpelstiltskin. Hopefully, this will create an original and personal work of art, if certainly within a tradition. One fairy tale happily reached the London Art Biennale in 2022.

Right, –. Material Transformation, 2018. Photo by Stefano Baroni.

After Pinocchio, Sculpted Fairy Tales.

Bronze is an expensive business, though, which only partly turned me back to ceramics. Many argue that the ceramicist’s particular art is a different calling from the sculptor’s, certainly with truth both in the sought purity of aesthetics, “cleanness” critics call it, and that often mysterious mastery of glazes. Yet I have always loved crossing or joining disciplines, as Chagal or Picasso defied stereotypes, in ceramics as much as painting, always with a sense of breaking free.

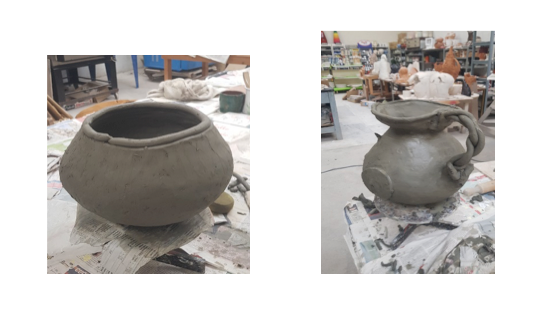

I had lost any schoolboy skill in “throwing” a work on that potter’s wheel (if I ever mastered it), so I turned to one of the oldest, simplest ceramic techniques – the coil pot. This is an easy process to learn: laying out strands of wet clay, hand-rolled or squeezed from a press, shaping a base, or cutting a shape with a stamp. Then, lay the clay tubes around and on top of each other, “closing” them together with a flat tool or your fingers, keeping the symmetry as you go. The keys are calm and confidence. The enemy is size because if you make the thing too big while the clay below is too wet, it will sink down on itself, so patience is required (not my greatest virtue, unlike ever patient Rascal).

In wanting to unite utility with Art, in the form of practical ceramics, but also “illustrating” and telling stories, the steady process of building the coil pot is perfect. You can easily reshape the body as you go, discovering forms, too. So to sculpting outer elements, such as “bas or haute relief,” namely working forms into a surface or raising them above it, or binding separately sculpted pieces and a handle onto the main surface.

There comes that most vital of tools–slip–just old, dried clay mixed with water to make a super glue, to stick together clays of differing dryness with the help of little scorings on the joins. You cannot just add water to wet clay because it dissolves, and you do need knowledge of what is possible. Any handle, for instance, must be thick enough to cleave to the clay body and not crack or break under its weight. It can break, either in the kiln, the potter’s essential cooking oven, or snap off when you try to pick it up and pour some Smoking Bishop.

My first attempt was, in fact, not literary, not least because the ancient Etruscans left no written literature. Instead, it arose from the astonishing coloured frescos I had seen on the walls of the 2000-year-old Etruscan tomb of “The Infernal Charioteer” at Sarteano near Rome. Another indispensable tool became a long metal needle, which was used to etch or draw into the clay, almost fresco style. In either copying or free invention, you can embed cleaner lines, which will also guide the paintbrush later. In any literary vein, you can also etch words directly into the clay, therefore writing into your own sculpture.

So comes that first “firing,” cooking the work for a day or so, as my friend Rascal waited ever patiently in the studio, too, to what is called the primary “biscuit” stage. Whether successful or not, hand-made, mine often had errors or could always be better (any artist’s plaint); it is hard to convey the joy of giving reign to your creativity. Living by it is an entirely different matter.

So once out of the oven again comes another deliciously creative and magical process, colour, in painting and further “illustrating” any work. Here, the art of the professional ceramicist diverges most significantly from the sculptor’s, I think, in a way that does point to a different aesthetic aspiration, too. In the mastery of glazes, colour’s basic relation to form is also essential. I would not dare teach what it can take years to master, but first, after all, comes both experimentation and study. Glazes, which you often dip whole works into, have their own possible colours and veneers, too, from mat to a high gloss or “cracked” textures. However, unlike ceramic paint, the kiln glazes will also react chemically with each other to produce completely unexpected effects.

Some uncertainty is true of firing painted works, too, in this case, an ever-evolving palette of ceramic paints called Engobe. In that sense, unlike finishing a painting under the naked eye, ceramic is always both an experimental and semi-interrupted art since you can never quite see the finished result before a second or perhaps third firing. Although there are more and more precise palette charts of finished colours available in a good studio, if you get the wrong overall (blue or beige), it can be disheartening enough to make you want to smash the thing. Writing, too, begins experimentally, and many have abandoned or torn up their own work to start again. There are many different techniques available, too, but also special and rather expensive final metallic finishes in solution, in the likes of gold, platinum, copper, bronze, or Mother of Pearl. These are then fired a third time to achieve even more startling effects.

So to that final result: the second Sarteano jug was still somewhat rough and ready, especially the spout, and, like looking at each other, symmetry naturally pleases the eye. Yet its success, I hope, is its vibrant colours, fun, and creativity. Delightfully, too, it sold, and it was Picasso who said Artists must sell, not only to speak but to make more Art!

So now came a first “literary” work, though, and one inspired by a writer and poet Dickens certainly revered, having fought so hard to protect his birthplace in Stratford: Shakespeare. I studied and loved Shakespeare, but after university, I went to the British-American drama school in London and was then also House Manager of Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre nearby, which glories in producing Shakespeare’s more magical work.

“The Globe-Tempest Jug,” so called, is based in detail on one of my favourite plays, The Tempest. Although containing technical elements of other jugs, the process involved a new one. First, I made the base to evoke that original wattle and daub Globe Theatre in London, recreated by the American actor Sam Wanamaker and echoed around the world, from Rome to Toronto. As a journalist and blogger, I often reviewed plays at that wonderful replica in Southwark, and I was lucky to scoff the delights of opening night eats, too, from the neighbouring Swan restaurant. My little theatre was not done in coils, but thick-cut clay rectangles formed into an octagon and joined with slip.

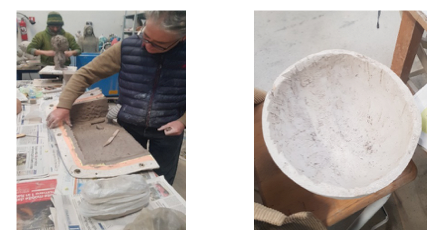

But the main body, essentially a Globe or World, also partly used in “The Christmas Carol Jug,” most breaks from the coil pot technique. It is made by pressing wet clay into a big mold, already there in my semi-public studio in Pietrasanta, Francesconi. Formed in plaster and with complex sculptures also with silicone linings nowadays to preserve detailed forms, molds are the Life Preservers of the sculptor’s art. That essential stage in preserving or copying clay and plaster sculpture and “casting” it into other forms, from wax to bronze, in that “lost wax” method. You see them everywhere in the workshops and foundries of Pietrasanta, in sizes from the small to the quite gigantic.

Since that hollow Globe was rather large, I had two basic problems: keeping it together with plentiful slip and sitting it on that octagonal base without crushing it completely. Once again, patience. There was a third problem, which forgetting about can lead to total disaster: you cannot leave closed air pockets inside, especially that open “Theatre” base, because the piece can crack in the kiln, even explode. “Una bomba,” they call it in my melodramatic Italian studio: a bomb. Again, that etching needle came to the rescue to pierce fine holes through the drying clay to let out any trapped air.

I then cut a circle into the top, made a rim and spout in the rough shape of Shakespeare’s ruff, and I hope with some handle on the lot, added the handle. Because of the size and the strength needed, with the prevailing sea themes in The Tempest, it had to be a chain and anchor. That became the inspiration for the handle on my Dickens jug, too, representing that horribly hefty chain forged by Jacob Marley’s misdeeds in life. Talking of misdeeds, though, in a proof with a much smaller Globe mold, I had made the mistake of throwing the kitchen sink at it. It was an unsettling experimental mess, although the “theatre” base is actually better.

With my second version, I wanted both to illustrate keys to the play and find personal meanings, too, the artist’s hidden signatures, along with a much cleaner ceramic aesthetic. Using both haute and bas-relief and drawing into the clay came seagulls, clouds, a map, and a sinking ship. Also, the outlines of the British Isles, Italy but Corfu too appeared, the generous Greek Isle a few eccentrics claim is where The Tempest is set, but where I used to go to write and Rascal and I adopted each other. I abandoned writing words or poetry into it almost completely, only inscribing the side and rim with Prospero’s famous appeal to the more tolerant spirits of any audience: “As you from crimes would pardon’d be, Let your indulgence set me free” (Shakespeare Epilogue. 19-20). I chose two basic colours, white and a kind of glittering blue, with little touches of black, under a high gloss glaze. So, pop it back in the oven and pray.

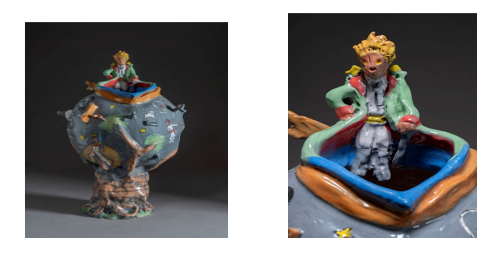

While it’s in the oven, with the magic spirit of a coming story in mind, perhaps to jump ahead to future results but strong literary inspirations too. That smaller mold for the proof had already given me another idea, inspired by Saint-Exupery’s great philosophical fable, “The Little Prince.” That smaller globe could be one of the strange Prince’s other planets, sitting on the base of a mysterious Baobab tree, and I had seen several in Africa crowned with a sculpture of the stylish Prince himself. Since Exupery had also illustrated his fable so perfectly, my creation would certainly be more of a work of copying to capture and celebrate a spirit, perhaps more lemonade or milk than a wine jug.

For a wine jug especially, though, I had also long hatched the idea of “illustrating” not a story but a poem, filled with images of the potter’s wheel and clay itself–The Rubaiyat of Omar Kayaam, by a 16th-century Persian author, but in a famous European translation by Edward Fitzgerald. That astonishing opening, “Awake, for morning in the bowl of night hath flung the stone that sets the stars to flight” (1), had powerfully lassoed a youthful imagination and remained. So, too, are the gloriously haunting and exotic illustrations by Edmund J Sullivan. For the basic form, I would try to echo, with that coil pot technique, a beautiful 18th-century bronze Persian wine jug.

After The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, Edward Fitzgerald, 1859. Photo DCD. Right, Edmund J. Sullivan’s illustration to verse 26 of Fitzgerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1913). Scanned by George P. Landow for the Victorian Web.

The Rubayaat’s long, exotic mediation on God, Philosophy, Art, and life and death, with Dickens’s Christmas Future in mind, too, is an almost Sufi-like hymn to poetry, tolerance, love, and women. It is also, while containing its own pleas to moderation, perfect as a song to various kinds of intoxication and wine. Like the second Shakespeare jug, I also wanted much cleaner paints and glazes, using only touches of those third, more exotic finishes, here copper.

We all need creative breaks, too, even from great literature, and fun and play are just as important to me as serious meanings or exact illustrations. Especially with ceramics, I equate pottery to cookery, both following and abandoning “recipes,” so out would pop “The Copper Pot,” a celebration of food and the arts of the kitchen.

But as for my cooking Shakespeare wine jug, would it be true to my ambition, at once aesthetic and worthy of honouring a literary titan while being personal too? Well, I liked it, certainly more than my first, especially the translucent blue of the handle, even if my Globe theatre got a little squashed.

Through all this work and learning and making my other jugs, it was, of course, December and Christmas that churned my thoughts again. That time of year, thanks to Dickens, is when poor old Marley usually starts to groan from my own internal door knocker. Whether you love or hate Christmas, that is always a significant, often painful time of year; the shame of The Christmas Carol jug had already started to grow from my other experiments. The main globe style was there already. The prevailing colour would be black to find the light, but what of a sturdy and illustrative enough base? Perhaps, in a similar reference to a Globe theatre, a Dickensian or Bob Crachet-esque top hat. Why not?

I let my hat dry well enough to support just a clay half-sphere this time (you can see the line), then turned back to the coil technique, building steadily on top, before attaching Marley’s huge chain handle. But what would this eccentric jug show, or practically give forth, to celebrate the original story: water, wine, even the milk of human kindness? That thought inspired the huge spout, in a hand holding an old-fashioned drinking horn but emerging from a dripping candle (candles are all over the tale since light is such a prevailing metaphor). Well, A Christmas Carol is at once a warning and reaffirmation of life, pleasure, and generosity.

So generally, though, in dominant size or particular detail, how can Dickens’s wonderful story be best illustrated? Tiny Tim’s crutch by the Grim Reaper’s scythe, that ever-ghostly door knocker, or peeling Christmas church bells and thrown open windows to wake Scrooge to joy and open-heartedness? In that, the original and several reinterpretations were competing in my head: the black and white Alastair Sim film, Disney’s Ebenezer McDuck, Scrooged, and even The Muppets Christmas Carol. One of my favourites is the musical Scrooge, with Albert Finney.

In the end, I stuck the most to that original illustrator, John Leech. Those three Spirits, not actually called ghosts, had to be there. That Spirit of Christmas Past, a kind of distorted child, yet feminine presence shimmering with light, flying Scrooge through the night air or around my globe. That ebullient Spirit of Christmas Present, somewhere always in green, sitting strangely on the mantlepiece of my imagination, surrounded by plenty–turkeys, ham, sausages, presents–laughing and thundering at Scrooge. That ominous spirit of all our futures, caught in skeletal form inside his cowl, pointing terrifyingly towards Scrooge’s grave and warning about what you leave behind.

So, with bas and haute reliefs and that etching needle, too, I started having fun finding other little windows to the story. So came Tiny Tim, carried on his father’s shoulders, into a far poorer but happier, more loving Christmas table than Scrooge can set. Then came begging or giving hands, Church bells, impressions of the Fezziwigs’ lovely parties, but also those ever-present and broken figures of Ignorance and Want, incarnated as broken children. Then, to painting it: not too much, putting in touches of colour, and a second, then final and third firing, in this case with Mother of Pearl. Once again, waiting for the kiln’s mysterious works, like whether the turkey will brown nicely or burn.

Is it a success? Well, that is for any “audience” to judge. Especially on a predominantly black base, the Mother of Pearl obscures some of the relief details and colours, but it also softens my sculpting mistakes and gives it a shimmering translucence. This is so appropriate for Christmas decorations; in fact, when I showed it to a collector dressing a splendid Christmas tree, they generously offered to buy it. Well, it is startling, very hand-made, decidedly eccentric, perhaps a kind of Dickensian folly. Bah, Humbug! Perhaps a little mystifying if you don’t know the story, as many Italians don’t. But essentially, it is what it is: evocative, creative, and a celebration, indeed resisting any cultural cancelations, which gave me huge pleasure to make. Ultimately, like all my sculpted ceramic series, it was meant to help me find my own flow and inspiration, but for others, to remember, discuss, and share some very great stories indeed.

- “Clay is the Life; Plaster the Death; Marble and Bronze the Resurrection” (Qtd. in Catherine Moriarty, “The Absent Dead and Figurative First World War Memorials” 37). ↩︎