The Reception of Charles Dickens’s Christmas Stories of the 1840s in Russia up to 1917

Contributed by Renata Goroshkova, a teaching assistant from St. Petersburg State University, Russia. She is now finishing her dissertation on Dickens’s Christmas stories of the 1840s.

Charles Dickens has always been highly popular in Russia. His works appeared in Russia as translated versions or recasts just one or two years after first being published in England. The Christmas stories of the 1840s have had a very special influence on Russian readers. These stories caused a stormy debate in the Russian critical periodicals of the nineteenth century, as well as leading to diametrically opposite responses – from humanist to antifeminist. In this post I will give a short overview of literary criticism of the nineteenth century to introduce English readers to the reception of the Christmas stories in Russia up to 1917.

Charles Dickens has always been highly popular in Russia. His works appeared in Russia as translated versions or recasts just one or two years after first being published in England. The Christmas stories of the 1840s have had a very special influence on Russian readers. These stories caused a stormy debate in the Russian critical periodicals of the nineteenth century, as well as leading to diametrically opposite responses – from humanist to antifeminist. In this post I will give a short overview of literary criticism of the nineteenth century to introduce English readers to the reception of the Christmas stories in Russia up to 1917.

Critics writing in Russian and English periodicals of the nineteenth century disagree with each other in terms of the merits and significance of the Christmas stories. A comparison which can exemplify this best is found in the following two extracts. In 1844, after the publication of A Christmas Carol, this response appeared in the Westminster Review:

The secret of Dickens’s success doubtless is, that he is a man with a heart in his bosom. […] He has an eye of a Dutch and also of an Italian artist for all external effect. […] Dickens has, beyond this, a strong perception of physical beauty, and also a beauty of generosity. […] But with all this, he is not an imaginative writer, he is not a philosophical writer; he pleases the sensation, but he does not satisfy the reason; he pleases and amuses, but he does not instruct; there is a want of base, of breadth, and of truth; and therefore, though he is probably the most widely-popular writer, he is not a great writer. The great elementary truths on which man’s physical well-being, and consequently his mental well-being, must depend, he apparently has not mastered. […] The impression which his works leave on the mind is like that with which we rise from the perusal of the ‘Fool of Quality’ – that all social evils are to be redressed by kindness and money given to the poor by the rich. This, doubtless, is something essential; but it is only a small part of the case. The poor require justice, not charity. [1]

The author then proceeds to a sharp criticism of A Christmas Carol:

A great part of the enjoyments of life are summed up in eating and drinking at the cost of munificent patrons of the poor; so that we might almost suppose the feudal times were returned. The processes whereby poor men are to be enabled to earn good wages, wherewith to buy turkeys for themselves, do not enter into the account. [2]

The understanding of A Christmas Carol in Russia at this time was quite different. In the literary and socio-political journal Sovremennik (Contemporary), founded by Alexandr Pushkin, we can find these words:

The Law is not the highest level of humanity; after this level there is love and self-sacrifice. […] When there is no heart, the mind always tries to fill this shortcoming and explains clearly that you have the full right not to have a heart. [3]

The author of this review admires Dickens’s talent, which ‘Didn’t want to get out of the art – and didn’t do that, […] and did not get carried away by boring philosophical digressions’. [4] In addition, the reviewer appreciates Dickens’s didactic abilities:

Dickens wanted to plant questions in the soul of the reader, which if we solve them and progress from conclusion to conclusion, will bear much fruit. […] These questions are true seeds that will give harvest, according to the soil in which they were sown. [5]

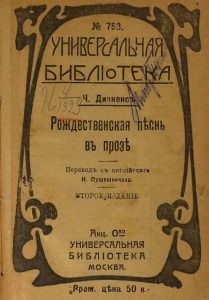

In Russia, Dickens’s Christmas stories were actively read and intensively interpreted producing curious results; from 1844 to 1917, forty reviews and critical articles about Dickens’s Christmas stories of the 1840s were published. For example, A Christmas Carol was not only translated into Russian many times and reprinted widely, but also had seventeen literary retellings (for example, Scary Visions or The Resurrected Soul by V. Tolstaya,[6] or The Old Miser. English Fairy Tale [7]); The Chimes and The Cricket on the Hearth were reprinted more than fifteen times each; The Haunted Man eleven times; and The Battle of Life ten. ‘Russian people are closed to his realism, they like his humanity, they could feel and understand his sensitivity towards the voices of life’, wrote K. Arsenyev in his article, which was dedicated to the centenary anniversary of Charles Dickens’s birth. [8]

In 1849, only one year after the publication of The Haunted Man in England, a review of this story appeared, again in Sovremennik:

Dickens should take the place of the most remarkable European novelist of the newest time. This inalienable right he has acquired not because his works are characterised by artistic merit. The reason is that all of them without exception are permeated by warmth of true feeling and humanity, without which any talent could not reach success. All the outlandish, rude or ignorant find in him a strict judge; all suffering, fallen or humiliated meet deep sympathy. He knows that there is no congenital evil, that the remains of the true feelings always sleep in the depths of the strayed heart. Every time, Dickens reminds puritan England that intolerance and cruelty of the heart are shameful to those who themselves are not alien to that society, among which these evils and crimes unfold. [9]

However, we can also see typical social mores for that time:

The author of this review claims that The Haunted Man is the weakest story in comparison to the others stories from this Christmas cycle. In this story the woman personifies the idea of wisdom. Letting the woman play the main role? We cannot forgive the famous novelist for this. [10]

In another journal named Zhenskoe Obrazovanie (Women’s Education), we find this:

This book is definitely not for children. No matter how strong the children’s nerves are, they cannot stand Dickens’s Christmas stories: so much in them is terrible and will act painfully on their imagination. But these stories are in the highest degree humane in their nature. [11]

The theme of Christmas entered Russian literature due to Dickens, giving birth to a specific genre (referred to as ‘Svyatochnaya Istoriya’ in Russian). Dickens had a great impact on many Russians writers such as Dostoevsky, Leskov, Shmelev and Pasternak, who developed and transformed the devices of Dickensian Christmas prose. But that is another story…

Notes

[1] ‘A New Spirit of the Age.’ Westminster ReviewII (1844): 374.

[2] Ibid. 376.

[3] Kronberg, I. ‘The Christmas Stories of Dickens.’ Sovremennik [Contemporary] 2.3 (1847): 5. (Translation mine)

[4] Ibid. 18.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tolstaya V. S. Scary Visions, or The Resurrected Soul. Moscow: M., Posrednik Publ., 1896.

[7]The Old Miser: An English Fairy Tale. St. Petersburg: Skazki, predaniya i legendy vseh stran [Fairy Tales, Stories and Legends of All Countries], 1874.

[8] Arsenyev K. ‘Two Anniversaries.’ Vestnik Europy [The Messenger of Europe] 2 (1912): 425. (Translation mine)

[9] ‘The Haunted Man. A New Christmas Story by Dickens.’ Sovremennik [Contemporary] 14.3 (1849): 45-47. (Translation mine)

[10] Ibid. 48.

[11] ‘The Christmas Stories of Charles Dickens.’ Zhenskoe Obrazovanie [Women’s Education] 9 (1886): (Translation mine)