Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Dickens and the Underdog

This post has been contributed by Catherine Burgass, a Lecturer and Honorary Research Fellow at Staffordshire University with a specialism in local literary studies. She also teaches at Keele University Continuing Education.

The use of animal metaphors for mechanical or human subjects is a common literary trope. The figurative richness of Dickens’ prose means that such metaphors are extended and expanded in his perennial project to highlight the plight of the underdog.

The first well-known example is from Bleak House where Jo, epitome of the disenfranchised, is chivvied from pillar to post by the powers that be until he inevitably shuffles off this mortal coil. Before we meet Jo we are treated to a viewing of his habitation, Tom-all-Alone’s:

these tumbling tenements contain, by night, a swarm of misery. As, on the ruined human wretch, vermin parasites appear, so, these ruined shelters have bred a crowd of foul existence that crawls in and out of gaps in walls and boards; and coils itself to sleep, in maggot numbers. (272)[1]

This description arguably plays to Victorian middle-class anxiety around the working classes: vermin, parasite, maggot – fast-breeding, disgusting, infectious. And Jo, when we meet him, is referred to as a ‘creature’:

It must be a strange state, not merely to be told that I am scarcely human … but to feel it of my own knowledge all my life! To see the horses, dogs, and cattle go by me and to know that in ignorance I belong to them and not to the superior beings in my shape, whose delicacy I offend! (274)

Although Jo is identified with the animal, these are useful domestic beasts – indeed, the associated ‘bovine’ indicates extreme placidity. However, the worm may turn and the dog may bite and, just in case you are missing the point, Dickens continues:

Jo, and the other lower animals, get on … as they can. It is market-day. The blinded oxen, over-goaded, over-driven, never guided, run into wrong places and are beaten out; and plunge red-eyed and foaming, at stone walls; and often sorely hurt the innocent, and often sorely hurt themselves. Very like Jo and his orders; very, very like! (275)

Jo is further demoted from the animal to the vegetable – first his clothes, ‘like a bundle of rank leaves of swampy growth that rotted long ago’ (686), then his person, ‘so like a growth of fungus or any unwholesome excrescence produced there in neglect and impurity’ (687).

When Jo is offered bread and coffee by the kindly Woodcourt, ‘he eats and drinks, like a scared animal’ (691). And in spite of Woodcourt’s compassion, Jo has been fatally reduced by an inhospitable society: ‘He is of no order and no place; neither of the beasts, nor of humanity’ (696). There is now nowhere to go except to his Maker and Jo dutifully expires in a superbly pathetic death scene.

The iniquities of industrial capitalism are then tackled in Hard Times, where the reduction of man to his function is symbolised by the conventional metonymic reference to the workers as ‘hands’. Animal metaphors are applied to Coketown in another frequently quoted passage:

It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. (18)[2]

The serpent inevitably recalls the Biblical original, another image with which to conjure fear and loathing. The elephant, however (a popular exotic animal in Victorian fiction), [3] is more to be pitied than feared. The novel decries the dehumanising and traumatic effects of industry and utilitarian thinking on bourgeois and proletariat both, encapsulated here in the plight of the elephant.

The last piece, ‘A Plated Article’, is less well known. Published in Household Words (1852), it describes a visit to the Spode Works in the Staffordshire Potteries. It features, bizarrely, a talking plate and a lengthy passage which prefigures the machinery in Hard Times – not animal, strictly, but certainly animated:

And as to the flint, don’t you recollect that it is first burnt in kilns, and is then laid under the four iron feet of a demon slave, subject to violent stamping fits, who, when they come on, stamps away insanely with his four iron legs, and would crush all the flint in the Isle of Thanet to powder, without leaving off? And as to the clay, don’t you recollect how it is put into mills or teazers […] and is then run into a rough house, all rugged beams and ladders splashed with white, – superintended by Grindoff the Miller in his working clothes, all splashed with white, – where it passes through no end of machinery- moved sieves all splashed with white, arranged in an ascending scale of fineness (some so fine, that three hundred silk threads cross each other in a single square inch of their surface), and all in a violent state of ague with their teeth for ever chattering, and their bodies for ever shivering![4]

The imagery and syntax emphasize the thumping monotony of the industrial environment. Here the workers do not ‘live’ on the page like Stephen Blackpool and Jo. They are mentioned only briefly as experts in their craft; it is the process and product which take precedence. This was not a state of the nation diatribe, it was a ‘factory tourist tale’, an altogether lighter affair which also functioned as PR for the industrialists.[5] Dickens nevertheless manages to allude to the conditions in which men, women and children worked, sickened and died by transferring both brutality and suffering to the machines, sparing the industrialist’s (in this case William Copeland) blushes, unless he cared to read between the lines.

It may be that some of the images of animal suffering had their origin in Dickens’ observations of his pet dog Timber, who was intermittently plagued with fleas.[6] In a long letter from Italy in the summer of 1844 Dickens wrote:

I don’t know what to do with Timber. He is as ill-adapted to the climate at this time of year as a suit of fur. I have had him made a lion dog; but the fleas flock in such crowds into the hair he has left, that they drive him nearly frantic…. Of all the miserable frights you ever saw, you never beheld such a devil.[7]

Happily, unlike Jo, Stephen Blackpool et al., ‘the little dog lived to be very old and accompanied the family in all its migrations.’[8]

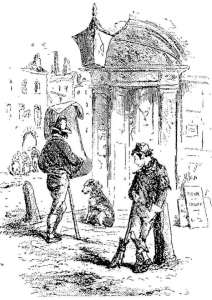

A band of music comes and plays.

Jo and the drover’s dog listen to it with

much the same sort of animal satisfaction.[9]

[1] Charles Dickens, Bleak House (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985).

[2] Charles Dickens, Hard Times (London: Chapman & Hall, 1905).

[3] See Kurt Koenigsberger, The Novel and the Menagerie: Totality, Englishness, and Empire (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2007).

[4] Charles Dickens, ‘A Plated Article’ (Stoke-upon-Trent: W.T. Copeland, undated), pp. 10-11.

[5] For an account of ‘factory tourist tales’ see Catherine Waters, Commodity Culture in Dickens’s Household Words: The Social Life of Goods (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 83-99.

[6] See Mimi Matthews’ blog: https://mimimatthews.com/2016/12/09/charles-dickens-and-timber-doodle-the-flea-ridden-dog/

[7] The Letters of Charles Dickens I., ed. Georgina Hogarth and Marnie Dickens (London: Chapman & Hall, 1880), pp. 109-110.

[8] Ibid. fn. p. 67.

[9] Original illustration by Phiz from: http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/phiz/bleakhouse/11b.html.

Very much enjoyed this cogent piece of writing. I was reminded of some of Shakespeare’s animal imagery — in most cases threatening and/or derogatory.

I also recall (from some research I did years ago) that in a manual for Roman farmers (by Columella???) in a hierarchical list of possessions human slaves are at the bottom — well after livestock; & machinery, even.