“The Objectionable Dog”: Dog and Master as Metaphor in Little Dorrit

This post has been contributed by Clara Defilippis. Read her first post for the Dickens Society blog, ‘Gift-Giving in the Proper Dickens Spirit’, here. You can also read Molly Katz and Erin Horáková’s post about dogs in David Copperfield here.

A flurry of short encounters with minor characters flood the pages of Dickens’s novels, and upon first glance these characters may seem to have little or any connection to the general plot, major characters, or message of the novel. In Little Dorrit, Mr. Henry Gowan’s wrestle with his vehement dog Lion, who was provoked by the villain Blandois, provides the reader with an interesting sketch, but this dog does not seem to be much more than an opportunity to illustrate Gowan and Blandois’s evil natures. Earlier in the novel, Clennam’s hatred and disgust for Gowan colors the narration of Clennam’s first meeting with Mr. Gowan and Lion as man and dog. In both instances, this disparaging representation of the usually revered companionship between man and beast forces the reader to question the significance of this dog within Little Dorrit. Rather than merely adding to the overall ambience, this “objectionable dog” (217) and his master are an important metaphor for various misguided relationships of loyalty and disgust between characters within Little Dorrit.

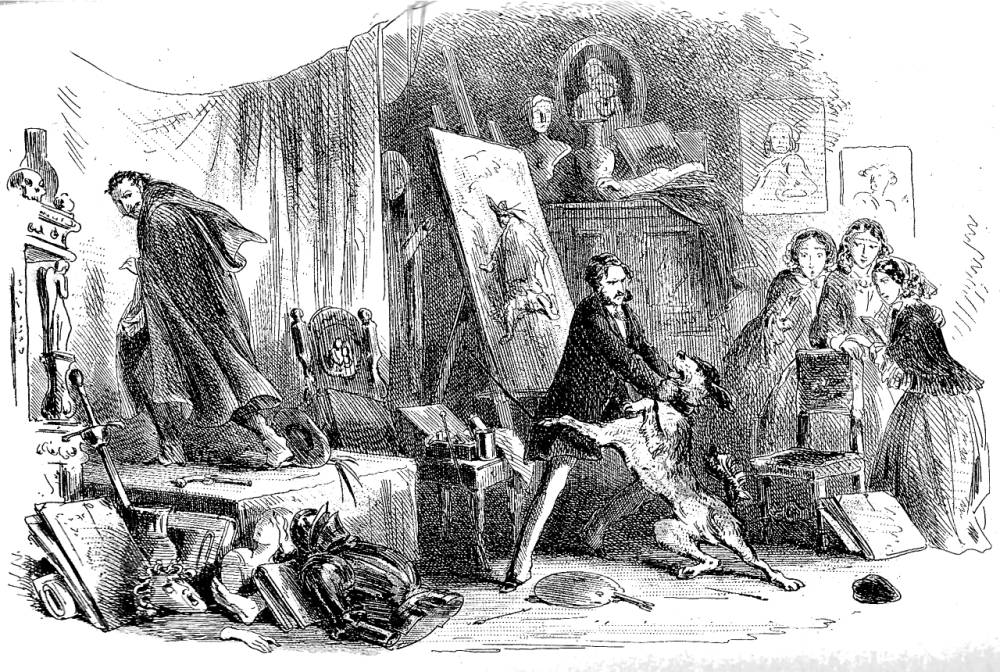

Instinct Stronger than Training by Phiz from Dickens’s Little Dorrit, Book the Second, “Riches,” Chapter 6, “Something Right Somewhere” (November 1856: Part Twelve). Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham.

The loyalty and love of a dog to its master has been championed through the ages as an example of virtue for man to follow. However, in Little Dorrit, Dickens represents loyal dogs and their masters in a negative light. While Lion usually obeys his master’s every command, Gowan beats the dog into submission when Lion attempts to attack the vicious Blandois:

[T]he master, little less angry than the dog, felled him with a blow on the head, and standing over him, struck him many times severely with the heel of his boot, so that his mouth was presently bloody. (512)

Even after this cruelty from his master, the dog preserves his loyalty and obedience, slinking away to the corner upon command to lick his wounds. The dog, who desires to protect the people he loves, is punished for recognizing the evil intentions of his master’s other companion and, ultimately, is poisoned and subsequently dies. In this example, Dickens brings to light the damage blind loyalty to a selfish and domineering personality can produce for an individual.

Just like Lion’s blind loyalty to his abusive master, in Little Dorrit many well-intentioned and ‘good’ characters esteem and aid egotistical masters like steadfast vassals, ignoring the failings of their charming ‘owners’. For example, the relationship between Gowan and Lion mirrors Gowan’s relationship with his wife Minnie. Despite Minnie’s parents’ concern for Gowan’s character and profession, Minnie blindly devotes herself to her husband and his whims. Even her childhood nickname, Pet, demonstrates her parallel significance to Lion who both overlook Gowan’s weaknesses, and, like her husband’s dog, Minnie loyally defends him as the best of all men.

Pet and Gowan are not the only example of a metaphorical dog and master in the novel. The good natured Mr. Sparkler follows Fanny around like a dog, and like Gowan, Fanny takes every opportunity to kick her silly and faithful admirer into submission. When speaking about her decision to marry Sparkler, Fanny describes her future resolve in terms similar to training a dog:

I shall make him fetch and carry, my dear, and I shall make him subject to me. And if I don’t make his mother subject to me, too, it shall not be my fault. (516)

Through these metaphorical examples of dog and master, Dickens emphasizes the vulnerable and misguided nature of loyalty and love between individuals who view themselves as owner and companion.

However, not all ‘dogs’ turn a blind eye to the abuse of their ‘masters,’ misreading domination as a form of love. At the beginning of the novel, young Barnacle speaks with Mr. Wobbler about a dog taken by his master in a cage on a train. Young Barnacle describes the dog’s malicious behavior:

Inestimable Dog. Flew at the porter fellow when he was put into the dog-box, and flew at the guard when he was taken out. (117)

He continues to explain that the master utilized the vicious nature of the dog to his advantage, having the canine participate in dog fights. In this instance, the dog misinterprets the intentions of the porter and guard as hostile, even though these men have no reason to do any harm to the dog.

In the characters of Miss Wade and Tattycoram, Dickens provides a figurative metaphor of the feral, backbiting dog who cannot distinguish between kindness and manipulation. Like Pet, Mr. Meagles has provided Tattycoram with a name, which he admits would be given to a dog or cat after Tattycoram leaves: “[W]ho were we that we should have a right to name her like a dog or a cat?” (336). Even Miss Wade describes Tattycoram as a dog when Mr. Clennam comes to visit them in France:

You are no higher than a spaniel, and had better go back to the people who did worse than whip you. (687)

Just like the dog that lashes out at anyone who seems to participate in its imprisonment on the train, Tattycoram’s uncontrollable temper places her in a subservient position to Miss Wade and, like the “inestimable dog,” Miss Wade goads Tattycoram and her blind rage into fighting Miss Wade’s personal battles of prejudice and malice. Tattycoram leaves the companionship of the Meagles only to be treated like a fighting-dog by her so-called rescuer.

Little Dorrit is full of additional dog imagery, such as Swiss St. Bernards, wealthy hunting dogs, or lowly street packs. In addition, Mr. Blandois calls Mr. Flintwinch a “dear deep old dog” (376), and Mrs. Merdle describes her moody and silent husband as being “dogged,” charging Mr. Merdle to “accommodate [himself] to society” (411). However, Dickens does not link other characters’ true loyalty, like Arthur Clennam and Amy Dorrit, with the imagery of man and beast. These characters and others, like Doyle or Young John, demonstrate clarity of vision which enables them to recognize the true evil and goodness of others, liberating them from submission to an unjust master. Little Dorrit sacrifices with a willing and open-heart for Arthur Clennam, not out of a sense of ill-begotten loyalty, but rather out of a knowledge of his worth, just as she can see the worth in Maggie or her Uncle Frederic. In Little Dorrit, Dickens does champion the love and loyalty of man and beast, but he emphasizes the need for dog and man to love freely and with clarity those ‘masters’ who strive to aid others and humbly accept their own faults.

Work Cited

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. New York: A.L. Burt Company.

Fascinating!!! Now I need to reread it. Great article.

Fascinating article! It really makes one think… I need to reread “Little Dorrit. Excellent