Interdisciplinary Dickens, 14-16 July 2017

The following post by Chris Dickinson and Laurena Tsudama provides a summary of the 2017 Dickens Society symposium, Interdisciplinary Dickens. Submit your abstract for our 2018 symposium, Dickens and Language, taking place 30 July to 1 August 2018 in Tübingen, here.

The 22nd annual Dickens Society Symposium took place at Boston University from July 14th to 16th. The event was co-sponsored by the Dickens Society and BU’s Center for Interdisciplinary Teaching & Learning at the College of General Studies and was organized by Natalie McKnight. The symposium’s theme was “Interdisciplinary Dickens,” and this led to an impressive, diverse collection of methodologies and approaches to Dickens’s work and life.

Figure 1. John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849-50.

The conference’s first panel, “Dickens and the Arts” opened with Suzanne Shumway’s discussion of the presence of woodwind players in David Copperfield and Little Dorrit and the “endangered class status” these musicians’ instruments of choice represent. Theresa Kenney analyzed Dickens’s review of Millais’s Christ in the House of his Parents using her knowledge of both Dickens’s aesthetic preferences and John Everett Millais’s painting. Laurena Tsudama argued that Dickens severed his professional relationship with Oliver Twist illustrator George Cruikshank in response to the latter’s overtly theatrical style, which clashed with Dickens’ growing desire to be taken seriously as an author. Although William Kumbier was unable to attend the conference due to the sudden cancellation of his flight, his paper, which argues that “in The Mystery of Edwin Drood the pervasive issues of composure and self-possession are played out through music,” was circulated throughout the panel.

The presenters on the “Dickens at/in Play” panel took a variety of approaches to the interesting subject. Sean Grass discussed how Dickens uses games and play in his novels and his characters’ development; using Pip’s card game with Estella as an example, Grass argued that, for Dickens, play is a method by which characters’ can cope with trauma. Michelle Allen-Emerson explored the presence of play and fun in David Copperfield. Marie-Amelie Coste examined Dickens’s use of sympathetic imagination in his writing. Robert Sirabian closed the panel with his presentation on the seeming paradox of “the discipline of play” in Dickens’s work and the ways play can create structure and meaning.

The second session of the day opened with a panel on the philosophical and political elements of Dickens’s oeuvre. Dominic Rainsford’s presented on disproportion in Dickens’s work; citing memorable passages in Bleak House and A Tale of Two Cities, Rainsford argued that Dickens used disproportion to evoke not only laughter but also political anger. Megan Beech discussed the parallels between Dickens’s and Harriet Martineau’s representation of “ordinary lives and people” as well as their vastly different views of political economy and labor reform. Sophie Christman Lavin argued that Hard Times uses Platonic idealism to critique the English education system, as represented by Gradgrind’s school board; Dickens unfavorably compares the English system to the Socratic model of education. Juliet John closed the panel with her presentation on the politics of interdisciplinarity: John argued that, while it is not without benefits, interdisciplinarity as practiced often organizes a hierarchy in which literature and literary culture are at the bottom.

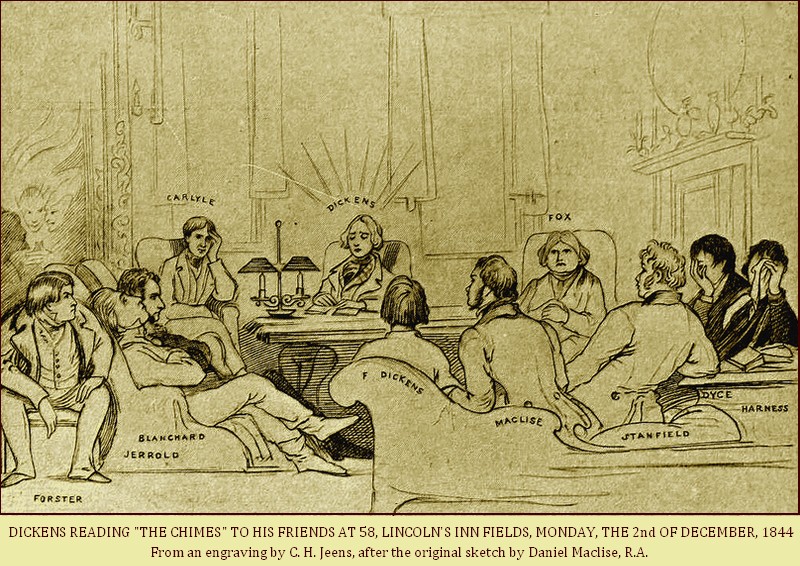

Figure 2. Daniel Maclise, Dickens Reading The Chimes to his Friends, December 1844.

The first panel in the 11:00 session dealt with Dickens and Religion. In her paper, Jane Kim used the parable of the Prodigal Son as a frame for reading David Copperfield. The frame proves to be ideal, as the novel features several ‘prodigals’ (Emily, David) who travel, experience loss, and return home. Susan Jhirad, herself a Unitarian for many years, presented on Dickens’s years in in the Unitarian Church and his close friendship with fellow author and Unitarian, Elizabeth Gaskell. These two bonded over the Unitarian ideal of ‘wanting to do something if possible’ for the poor and marginalized of English Society. Kathleen Bell, presenting on Dickens’s The Life of our Lord, argues that, contrary to most modern scholarship, Dickens believed in the divine nature of Christ since the text includes Christ’s miracles of healing. Bell argues that these scenes in TLOOL operate in the same way as scenes of healing from his novels. Finally, Christian Dickinson used Dickens’s anti-establishmentarian religious views as a framework for reading Bleak House, demonstrating how that novel satirizes ‘High-Church’, ‘Low-Church’, and Nonconformist sects.

In the 1:50 session, “Urban Dickens”, Leslie Simon argued that Dickens’s description of urban and domestic spaces draw upon the “pure math” movement, a popular trend in mathematics during his time. Dickens’s descriptions are not meant to give a precise image of a space, but rather an abstract impression due to their copiousness. Eva-Charlotta Mebius, discussing flood imagery in Dickens’s writings, argues that the antediluvian theme can be felt as far as Hard Times. According to Mebius, Dickens’s scenes of the city constantly waver on the edge of destruction, and the reader is never fully aware if they are in a pre or postdiluvian moment. The panel ended with Catherine Quirk’s paper on Dickens’s relationship with the Metropolitan Police, as seen through characters such as Mr. Bucket. After a brief history on the Metropolitan Police and the creation of the detective position, Quirk makes a comparison between characters like Bucket and Dickens himself, stating that both are “professional observers”.

Also part of the 1:50 session was the panel “Triple D: Dickens, Disease and Death.” Katherine Kim discussed the presence of decapitation and death in Dickens’s work, covering everything from ghosts to Jenny Wren’s cry, “Come up and be dead.” Galia Benziman adopted a psychoanalytic approach to examine mourning, melancholy, and dead mothers in Dickens’s novels, emphasizing how those mourned are made present through memory and images. Andre DeCuir concluded the panel with his presentation on Bleak House and the rise of germ theory; in particular, DeCuir explained how the notion of “animalcules” led to germ theory and discussed Dickens’s concerns regarding water quality and contagion.

Friday’s late afternoon panel, “Dickens, Chance and Melodrama”, opened with Daniel Siegel’s paper, which explored the uses of statistic-gathering software for literary analysis. Siegel, whose thematic analysis of Mr. Pegotty from David Copperfield originated from computer-generated statistics regarding when Pegotty appears in the text, asks if subsequent ‘human analysis’ is even valid. The panel concluded with April Kendra, a scholar of the gothic, who asked one very fascinating question: Is John Jasper of Edwin Drood, a vampire? Using 19th century vampire-lore and cultural beliefs as a framework for examining the character, Kendra argues that Jasper’s paleness and his apparent ability to move through walls mark him as vampiric.

Figure 3. Phiz (Hablot K. Browne ), “God bless me, what’s the matter,” Household Edition Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, p. 65

The first presenter of Friday’s final panel, “Dickens, Education, and Epistemology,” Masumi Odari explored the similarities between Dickens’s “educational theory,” particularly as represented in David Copperfield, and the work of Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, a prominent Japanese educator and educational theorist of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. Sheila Cordner discussed how Hard Times is critical of rote learning and argued that rote learning remains a feature of today’s educational systems; she also shared her experience organizing a service learning project in which students visited Boston’s Hale House and lead discussions with the residents on Dickens’s work. Angelika Zirker and Matthias Bauer co-presented on the subject of epistemology in The Pickwick Papers and Martin Chuzzlewit; in particular, they addressed how knowledge and ignorance are represented in Dickens’s characters and plots. Friday concluded with the Dickens Dinner at the Omni Parker House, where Dickens stayed during his second trip to Boston.

Saturday’s first panel, “Dickens on the Brain,” began with Adam Colman’s presentation on addiction discourse and pattern recognition in Bleak House. Colman argued that characters like Esther can make sense of their world’s repetitive, labyrinthian environments and plots while characters with addictive mindsets, such as Skimpole and Richard, remain stuck in the fog and haze. Margaret Rennix also focused on Bleak House, and she argued that Esther and Richard both exhibit “limited rationality”: they limit their options as rational actors by committing themselves to one purpose, but Esther has greater success keeping her commitment because she commits to a person rather than an ideal. Barbara McCarthy utilized the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to create psychological profiles of the primary members of the Pickwick Club. According to McCarthy, Pickwick is an ENFJ, Winkle an ENFP, Tupman an ISFP, and Snodgrass an INFP. Finally, citing Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and Great Expectations, Maria Bachman argued that Dickens was “prescient of 21st-century research on expectations”; Bachman explained that Dickens understood both readers’ expectations and the ways expectations (especially failed expectations) inform character development.

Figure 4. “Dickens on the Brain” Q&A.

In the second morning session, “Sociological Dickens”, Lydia Craig opened her talk by stating that Dickens “writes with a historian’s mindset”, noting various allusions to Wat Tyler’s 1381 ‘Peasant’s Revolt in both Bleak House and Pickwick Papers. These allusions are most pronounced in Pickwick’s Essex scenes, particularly when the eponymous hero is placed in ‘the pound’, equating him with a stray animal. Goldie Morgentaler then spoke about Dickens and family planning, contrasting the large, happy families of his early works to the incompetent and overwhelmed parents of his later novels. Morgentaler argues that this shift in Dickens’s positive view of large families makes sense, as he himself became a father of ten children the same year Bleak House was first published! The session concluded with Akiko Takei’s paper on Urania Cottage, Dickens’s charity home for fallen women. After reviewing the history and daily working of the Cottage, Takei concludes that the cottage was mostly a success, as 49 of the 56 residents were able to either emigrate and marry well, or stay without returning to prostitution.

Next was the “Dickens in/on America” panel, which commenced with Jerome Meckier’s presentation on Dickens’s encounters with American presidents. Meckier discussed Dickens’s meetings with John Tyler, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Johnson as well as his admiration of Abraham Lincoln. Iain Crawford presented on Dickens’s relationship with the American press, which experienced great growth in the 1830s; Crawford argued that, while Dickens criticized the tactics of American newspapers, his parodying of the press, especially in Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit, proved artistically generative. In the panel’s final presentation, Diana Archibald connected contemporary lamentations over the failure of so-called American exceptionalism with Dickens’s own disappointed expectations upon his first tour of America: while Dickens believed in America’s democratic ideals, he saw that hypocrisy often prevented American politicians and officials from practicing their professed ideals.

Figure 5. Edward Ardizzone, 1952. Megan Witzleben: “Wemmick departs from the stonework and divided space of the Gothic craze, yet keeps a private room for Pip.”

Saturday’s 11:10 session, “STEAM Dickens”, opened with a co-presentation by Susan Cook and Liz Henley, who used the modern ‘digital’ revolution as a lens for reading Dickens in the context of the Industrial revolution. The pair shared pedagogical techniques from the Industrial era to today, demonstrating how each generation is both suited to and educated to use the technologies of their time. Next, Christopher Keirstead spoke on the technology of air-travel, noting that in Household Words, speculative articles on flying machines avoided satire—an unusual move for the journal. Keirstead then shared a critical reading of the ‘flight’ scene in A Christmas Carol, in which Scrooge is given ‘a new geographical (and spiritual) perspective’. The session ended with Megan Witzleben, whose paper explored the ideals of class and domesticity which underlie Victorian architecture, ideals which provide a way of understanding the intersection between place and space in Great Expectations.

In the 2:00 panel on “Dickens, Friends & Family”, Lillian Nayder spoke on the ‘Miawberization’ of Dickens’s father John, arguing that the common comparison to David’s feckless friend is a dishonest one. In fact, Nayder stated that John himself inspired Dickens’s ‘magpie’ style of language, which combines elements of both high and low humor. Next, Mark Cronin spoke on John Henry Barrow, Dickens’s uncle, examining his work for possible influences. After analyzing Barrow’s novel, Emir Malek: Prince of Assassins, Cronin concluded that no direct influence could be seen. Michelle Mastro then spoke on the topic of parental influence, noting that Dickens often deals with anxieties regarding ‘moral inheritance’, or the fear a child has that he or she will inherit their parent’s vices. To Mastro, this fear is exemplified in Bleak House, a novel that deals with anxieties regarding both financial and familial inheritance. The panel concluded with David Paroissien, whose paper gave a comparative analysis of Dickens’s Child’s History with The Book of Common Prayer, noting that both take on ‘revisionist’ views of history and cultural bias regarding contemporary opinions of certain monarchical figures.

In Sunday’s 9:30 panel, “Dickens, Gender and Economics”, Margaret Darby spoke on ideas of reflecting and reflections in David Copperfield and the ‘biographical fragment’ connected to it. Darby analyzed moments of reflection and transparency in Dickens’s own life, such as when he was looked at through the window of the blacking warehouse where he worked, and then looked through a shop window at the pineapples he wished he could buy. The panel concluded with Douglas Scully, who focused on changing depictions of Nancy Sikes through various film adaptations of Oliver Twist. Scully argued that the character of Nancy embodies a ‘cultural text’, or the power a narrative moment has when embedded into the minds of the culture—many times, such ‘text’s are based on adaptations rather than original source material.

Figure 6. Oliver Twisted by J.D. Sharpe and Charles Dickens (2012).

The second panel of Sunday’s 9:30 session, “Dickens’s Afterlives,” opened with Emily Bell’s presentation on Dickensian biofiction. Citing recent examples as well as the 1849 novel The Battle of London Life; or, Boz and His Secretary, Bell explained that these works often displace Dickens from the narrative’s center and tend to concern themselves with issues of authorship and influence. Temitope Abisoye Noah discussed the presence of and connections between Dickens and parapsychology in Clint Eastwood’s film Hereafter, in which Dickens’s work and persona remain significant and positive influences on the protagonist, whose ability to communicate with the dead has long tormented him. Joseph McLaughlin argued that, while Dickens’s progressive rhetoric regarding poverty and inequality relies on pathos, today’s progressive movement must also recognize that purely humanist appeals are not enough; instead, McLaughlin suggests following Dickens’s lead by pairing humanist rhetoric with an emphasis on the practical benefits of reform. Maya Zakrzewska-Pim closed the panel with her presentation on the adaptation of Dickens for children’s literature; in particular, Zakrzewska-Pim focused on the novel Oliver Twisted and argued that it maintains the spirit of Dickens’s novel while making it more concise, altering its tone, and modernizing its characters.

In the conference’s final session, the “Words & Things” panel began with Dano Cammarota’s presentation on the relation between the “bow-wow” theory of language, coined by Max Müller, and Martin Chuzzlewit and Our Mutual Friend; Cammarota drew on passages from these novels to demonstrate how language was in flux in the mid-nineteenth century. Joel Brattin shared his analysis of Dickens’s proofs of A Tale of Two Cities and discussed the difficulty of making sense of problematic proofs that lack many variants. Colette Ramuz’s presentation on David Copperfield and mouth fetish examined “the significance of the mouth in male sexuality in Dickens’s novel”; in particular, she outlined the complex, erotic relationships between David, Murdstone, and Uriah Heep. Katherine Jackson also focused on David Copperfield: she argued that the use of objects, particularly cutlery (with which David associates himself), is an abiding concern of the novel and is meant to distinguish good, orderly households from bad, chaotic households.

This report concludes with the second panel on “Dickens and Religion”. Contrasting her analysis with the division between the ‘transcendent’ and ‘immanent’ frame offered by Charles Taylor in A Secular Age, Christine Colon argued that Dickens’s ‘boring’ characters participate in a life of ‘radical ordinariness’, living out authentic Christian beliefs through quiet sacrifices and wise decisions. In his paper, Hai Na argued that for Dickens, “’authentic religion’ rests on the idea of choice”. Na stated that Dickens’s view of Christianity was steeped in Romanticism, and that for him, authentic belief must be found outside the official institution of the Church. In the final paper of the session, Yuanyuan Zhu spoke on Dickens’s use of biblical allusions, particularly in works such as Hard Times; these allusions are used without too many radical religious or economic ideas in order to effect circumscribed change. While some allusions are used to expose and mock the falsity or wickedness of some characters, others instead describe moral characters or demonstrate how characters embody Christian principles.

As this report shows, the conference was interdisciplinary in every sense of the word. Dickens and his writings was approached from a number of different angles—religious, scientific, philosophical, pedagogical and even digital. The end result is a multi-faceted picture of an author who seemed to have written a bit about everything, whose opinions are inexhaustible as much as his work is inimitable.

Figure 7. Dickens’s portrait at the Omni Parker House in Boston, where Dickens stayed during his second trip to Boston and where the symposium’s Dickens Dinner was held.