If He Could Turn Back Time: Scrooge’s Missing Hours in A Christmas Carol

Contributed by Christian Sidney Dickinson, Baptist College of Florida

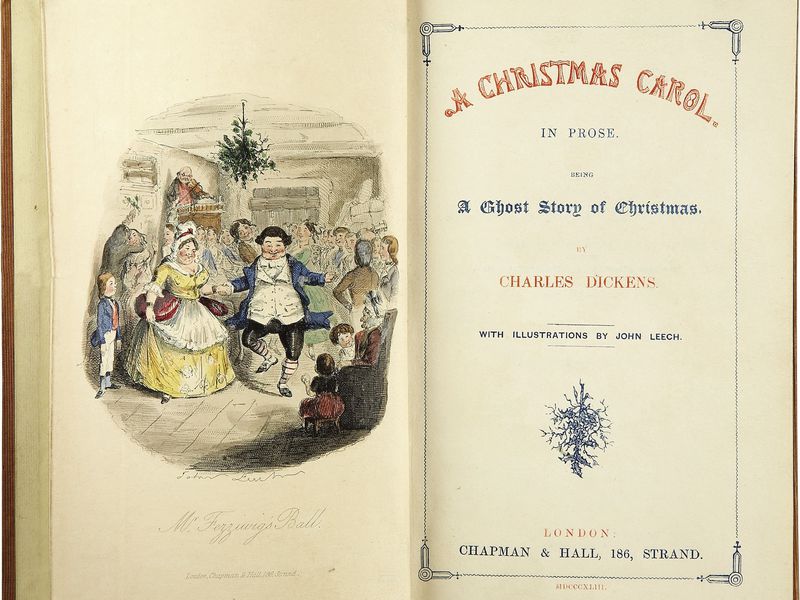

At the end of the First Stave of Charles Dickens’s Christmas classic, A Christmas Carol (1843), a disturbed Scrooge, after having conversed with the ghost of his long-departed (we know better than to say ‘dear’) business partner Jacob Marley, reels to bed in a state of benumbed stupefaction. He awakens while it is still night and listens intently as the chimes of a neighboring church-bell fall upon his ear:

To his great astonishment, the heavy bell went on from six to seven, and from seven to eight,and regularly up to twelve; then stopped. Twelve! It was past two when he went to bed. The clock was wrong. An icicle must have got into the works. Twelve! (28)

After an experiment with the repeater, Scrooge discovers that there is nothing wrong with the clock. He then wonders if he “[has] slept a whole day and far into another night” or if “anything has happened to the sun, and this is twelve at noon!” (28). But these speculations both prove to be equally unfounded. It really does appear that time, for Scrooge, has reversed itself more than two hours.

So—why does Dickens do this?

There does not seem to be a reason—at least, not narratively speaking. Obviously, if Scrooge wakes up on Christmas Day before his reformation, then the story itself would be meaningless. Of course, we know that the Spirits seem to have the ability to manipulate time. In the last Stave, Scrooge rejoices in this apparent fact:

“It’s Christmas Day!” said Scrooge to himself. “I haven’t missed it. The spirits have done it all in one night. They can do anything they like. Of course they can. Of course they can.” (83)

Yet, in this scene, why give the time at all? Why mention when Scrooge went to bed? In the previous Stave, we are told that Scrooge, after shutting up the counting-house, “took his melancholy dinner in his usual melancholy tavern; and having read all the newspapers, and beguiled the rest of the evening with his banker’s-book, went home to bed” (17). He meets Marley’s ghost soon after. Even taking into account an hour or two for Scrooge’s night-time perambulations, his conversation with Marley would begin at around eight pm. The scene itself is not a long one, yet we are meant to believe it has taken something like six hours. Why would Dickens, so careful about precise plotting, create such a glaring narrative conundrum?

As a scholar, I am left to conclude that the reversal of time given to us in this scene, since it serves neither to advance the action nor reveal something unknown about Scrooge’s character, is not simply an example of narrative spectacle (which is in no short supply in Dickens); rather, this moment serves as an important thematic sign-post, pointing to the primary message that Dickens is attempting to communicate through this most famous of stories: do good to and for others while there is yet time.

My evidence for seeing the reversal of time in Carol as thematically-motivated is two-fold. To begin with, anyone familiar with Dickens knows he loves to play with time. However, is there enough evidence that this experimentation can be seen as a thematic pattern in Dickens’s work? If so, then the claim above could be granted more validity through being part of an established trope. Fortunately, in examining moments of the use of clocks and time in Dickens’s work, a pattern does seem to emerge. This is particularly true in the Christmas Stories. For example, in The Chimes, Toby Veck has a vision of his own death and is instantly transported nearly a decade into the future:

The tower opened at his feet. He looked down, and beheld his own form, lying at the bottom, on the outside, crushed and motionless.

…“What!” he cried, shuddering. “I missed my way, and coming on the outside of this tower in the dark, fell down—a year ago?”

“Nine years ago!” replied the figures. (143)

Veck’s death, which eventually does turn out to be a fantastical vision, speaks directly to the themes of waste and regret that form the thematic motivation of the story:

“Who puts into the mouth of Time, or of its servants,” said the Goblin of the Bell, “a cry of lamentation for days which have had their trial and failure, and have left deep traces of it which the blind may see—a cry that only serves the present time, by showing men how much it needs their help when any ears can listen to regrets for such a past—who does this, does a wrong. And you have done that wrong to us, the Chimes.” (141)

The Goblin of the Bell, much like Marley’s Ghost, chides the protagonist of the story for his misuse of time. Of course Veck, very much unlike Scrooge, spends his time in past regrets rather than cruelty and selfish ignorance; but to Dickens, this distinction of motive does not matter. What both men share, and what both are condemned for, is a self-centered misuse of time—whether it be positive or negative.

The use of clocks and chronological time as a thematic symbol is seen again in another Christmas story, The Cricket on the Hearth. In one scene a Dutch Clock in the home of the Perrybingles strikes the time at important moments in the story; first at the beginning, and then at the beginning of the ‘Second Chirp’, when Mr.Perrybingle believes he has just seen evidence of his wife Dot’s infidelity:

The Dutch clock in the corner struck Ten, when the Carrier sat down by his fireside. So troubled and grief-worn, that he seemed to scare the Cuckoo, who, having cut his ten melodious announcements as short as possible, plunged back into the Moorish Palace again, and clapped his little door behind him, as if the unwonted spectacle were too much for his feeling (237-238).

The link between cuckoo (the bird in the clock) and cuckold (what John believes himself to be in this scene), is a well-established theme in English literature, going back to Chaucer.

Of course, no discussion of Dickens, clocks, and theme would be complete without a mention of that famous scene from Great Expectations:

It was when I stood before her, avoiding her eyes, that I took note of the surrounding objects in detail, and saw that her watch had stopped at twenty minutes to nine, and that a clock in the room had stopped at twenty minutes to nine … It was then I began to understand that everything in the room had stopped, like the watch and the clock, a long time ago. (58, 60)

The connection between the stopped clocks in Miss Havisham’s room, and the stopped life of Miss Havisham herself, is one of the most perfect examples of expressions of time reflecting a central theme. The number of examples of time as theme in his work suggest that this is a common Dickensian trope.

Having established this trope in Dickens’s works in a general sense, I now move to the particular connection demonstrated in A Christmas Carol: that Dickens’s experimentation with time speaks to his message regarding the importance of charity and service towards others. To support this connection, I turn to Stephen L. Franklin’s article “Dickens and Time: The Clock without Hands,” published in the 1975 issue of the Dickens Studies Annual. In his analysis of A Christmas Carol and time, Franklin says:

…the lesson Scrooge learns in his night of wonders is about the use of time … The emphasis on Christmastime as a special time leads only to this awareness in Scrooge: “I will honor Christmas in my heart and keep it all the year!” (iv). As soon as he gains this awareness, Dickens tells us “The Time before him was his own, to make amends in” (v). In no other work, except perhaps Bleak House, does Dickens connect Christianity so directly to the acceptance of time. (15-16)

By “Christianity,” Franklin is referring to the social gospel of Dickens, a Christianity which makes itself known through the charitable work and service one engages in on behalf of others. Franklin makes this clear in a statement soon after the one given above:

…when Scrooge says, “I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future” … he is commenting, not on periods of time or life, but on the temporal continuum … In this attitude [Dickens articulates his belief] … that Christian behavior results from conscious consideration of existence as a temporal mode. What Dickens rejects is a dwelling on the past or future for their own sakes, because such dwelling leads to misuse of time in the present.(16)

Orienting Scrooge to a “present”understanding of time is essential to his reformation, as his controlling vice, greed, stems from an obsession with the future. More accurately, from an obsessive desire to avoid future penury at all costs.

The necessity for a Christian understanding of linear time, ever-present and ever-active, is the message that Dickens wishes to communicate to readers through Scrooge’s experience of temporal reversal. Dickens’s message is clear: Scrooge was blessed to receive time back. But you, dear reader, will never be. As you have breath, use the time you have to do good for others— before the clock chimes twelve.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol, The Chimes, and The Cricket on the Hearth. Barnes & Noble Classics, 2004.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Penguin Classics, 2003.

Franklin, Stephen L.“Dickens and Time: The Clock without Hands.” Dickens Studies Annual, vol.4, 1975, pp. 1-35.

Chris Dickinson earned his Bachelor’s of English from the University of North Florida in 2005. After teaching for two years in Orange Park, he was admitted in the Master’s Program at Florida State University. This past December, he graduated with his PhD from Baylor University and currently teaches at the Baptist College of Florida in Graceville, Florida. His interests include the Victorian novel and its intersection with the religious sectarian debate in 19th century England.

Thank you for the nice write on Carol. I’ve read it many times, during and after the holidays, and have always noted Dicken’s irregularity with the timings of the ghosts. All of them seemed to be ahead or “behind my time”, pardon the pun. Would this be Dicken’s advising that watching the clock should be avoided? Or that things will come in their own time? Perhaps patience? It seems the future ghost actually goes back in time to midnight, where the first ghost was on time, the second ghost at 2. And even Marley himself appeared “after 2”. Am I missing something important?