Dispatches from the 26th Symposium: Charles Dickens and Peter Pitchlynn

Contributed by Spencer Dodd, PhD Student, Louisiana State University.

Recent years have seen significant scholarly interest in Dickens and race, a trend continued by the 2021 Virtual Dickens Symposium, which featured multiple papers analyzing Dickens’s works in the context of racial issues. While these papers covered an astonishing variety of topics, some focused on American Notes for General Circulation, Dickens’s account of his travels in the United States (1842). Dickens’s unflattering observations on American culture have long captured the interest of readers and scholars. His scathing critiques of American slavery and prisons, in particular, have started rich, ongoing scholarly conversations about these issues. While this blog post will touch on these topics, the focal point here will be Dickens’s encounter with Peter Pitchlynn in Chapter 12 of American Notes, an episode that figured in several papers presented at the symposium. The encounter in question took place on a long steamboat voyage from Cincinnati to Louisville and constitutes Dickens’s most direct engagement with a Native American culture.

Pitchlynn’s personal papers are today housed in the Western History Collection at the University of Oklahoma. One find from this archive, rediscovered by Philip Carroll Morgan in 2009, provides some fascinating context for the conversation between Dickens and Pitchlynn. This particular collection of Pitchlynn’s letters from the 1830-40s includes a letter from one James L. McDonald, a short-lived but brilliant Choctaw intellectual. The letter, which Philip Caroll Morgan calls “The Spectre Essay” recounts a hitherto unknown Choctaw legend about a proud warrior who narrowly avoids death at the hands of his spectral doppleganger. McDonald’s preamble to the story makes it clear that this tale of horror and defamiliarization is part of a larger dialogue with Pitchlynn about Choctaw letters, assimilation, and storytelling. McDonald, a staunch opponent of assimilation compared to Pitchlynn’s resigned pragmatism, held that the English language could not do the harrowing tale justice; despite the translator’s best efforts, some nuances are lost to the settler’s tongue (Morgan 47). The sting of incalculable loss shines through most clearly in the story’s epilogue. Thanks to his dog’s sacrifice, the warrior escapes from the spectre with his life, but he is forever changed. He becomes a living ghost, a hollow shell of his former self, cold, impenetrable, and soulless, who departs the Choctaw homelands forever to seek certain death. Perhaps, we can read this uncanny conclusion as reflective of the anxieties Pitchlynn and Dickens discussed concerning the fate and future of the Choctaw Nation. However, we can further contextualize this meeting (and the “Spectre Essay”) by considering Pitchlynn’s life and work.

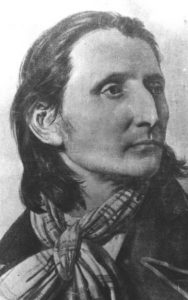

In 1806 Peter Pitchlynn was born in Mississippi to a Choctaw mother, Sophia Folsom, and a white father, John Pitchlynn. He attended boarding school and then university in Tennessee, returning to Choctaw lands after earning his degree. Although still a young man upon his return to Mississippi, Pitchlynn quickly became involved in Choctaw politics and statecraft. His rapid entry into politics reflected his intellectual talent and solid family connections, as well as the crisis facing the Choctaw nation in the 1820s and 30s: the looming threat of removal. Settlers had long coveted lands belonging to the “Five Civilized Tribes” (the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole: five powerful Southeastern Native groups), and the Jackson administration had taken a keen interest in enforcing these claims following the 1829 discovery of gold on Cherokee land. The Five Tribes had struggled to maintain their cultural identities while under increasing pressure to give up their ancestral lands. Between 1826 and 1828, Pitchlynn took part in a series of meetings to reshape the Choctaw nation into an organized state reflective of this balancing act. The resulting document, A Gathering of Statesmen, outlined the policies and constitution of the tribe in a codified, federal model primarily designed and recorded by Pitchlynn. Shortly after this, Pitchlynn realized that removal was inevitable and became an early proponent of relocating to Indian territory in what is now Oklahoma. In 1830, the Choctaw acquiesced to the U.S. government and relocated to Northeastern Oklahoma, which proved brutal and heartbreaking. However, removal also presented the opportunity for a fresh start in an unfamiliar land, facilitating further developments in statecraft and education. Pitchlynn took great interest in building up the nation’s educational and cultural infrastructure. Meanwhile, the U.S. government had reneged on removal-era deals involving Choctaw lands, and for the rest of his life, Pitchlynn periodically travelled from Indian territory to Washington D.C. to lobby for Choctaw interests. His 1842 meeting with Dickens occurred during a return trip from Washington.

The journey downriver from Cincinnati to Louisville was a prolonged affair, and the two men engaged in a long, substantive conversation. Pitchlynn made quite the impression on Dickens:

He spoke English perfectly well, though he had not begun to learn the language, he told me, until he was a young man grown. He had read many books; and. . . He appeared to understand correctly all he had read; and whatever fiction had enlisted his sympathy in its belief, had done so keenly and earnestly. I might almost say fiercely. (Dickens 137).

They seem to have bonded over mutual interests in literature and anthropology, though the scene is clouded somewhat by Dickens’s invocations of the “noble savage” archetype. Throughout, there’s a hint of paternalism to his wonder at Pitchlynn’s intellectuality and good taste. At the symposium, Rob Jacklosky pointed to Dickens’s wonder and delight that Pitchlynn had a card to send him. However, the connection between the two men was probably genuine. To paraphrase Katie Bell’s symposium paper, the America Dickens found mostly didn’t match what he had imagined (usually, for the worse), and his encounter with Peter Pitchlynn stood out as a positive memory. As both Bell and Jacklosky mentioned, Dickens’s mostly favorable (but arguably sensationalized and paternalistic) depiction of Pitchlynn stands in stark contrast to how he portrayed African American characters in American Notes as objects of revulsion. Dickens may have chosen the highlights of their long conversation and applied the “noble savage” lens to produce a more entertaining travelogue. Consider this exchange from later in Chapter 12: “A few of his brother chiefs had been obliged to become civilised, and to make themselves acquainted with what the whites knew, for it was their only chance of Existence. . . He dwelt on this: and said several times that unless they tried to assimilate themselves to their conquerors, they must be swept away before the strides of civilised society” (Dickens 137). With this, we can see how Dickens was melding the topics of culture, assimilation, and education in order to enlighten his readership about the plights of the Native Americans, but he was also falling into the “noble savage” trope. Pitchlynn’s work focused on striking a balance between assimilation and preserving Choctaw cultural traditions, and Dickens seemed to grasp the delicate nature of this balancing act.

Towards the end of their conversation, Pitchlynn expressed interest in visiting England and Dickens told him of “the chamber in the British Museum wherein are preserved household memorials of a race that ceased to be” which Pitchlynn connected to the crises facing his own people (137). Pensive, Pitchlynn notes that “the English used to be very fond of the Red Men when they wanted their help, but had not cared much for them, since” and soon departs, “as stately and complete a gentleman of Nature’s making, as ever I beheld” (137). And thus ends their conversation – the two men never met again, and Pitchlynn never ended up visiting England. I think we can recognize the importance of this encounter – a complicated moment of cross-cultural contact to consider as we grapple with the racial legacies of Victorian literature. As a final note, Pitchlynn’s lifelong struggle to compel the government to honor removal-era treaties entered an unexpected and much-belated new chapter last year, with the Supreme court’s decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy. 1842. Chapman and Hall, 1913. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/675/675-h/675-h.htm#page137

McDonald, James L. “Letter to Peter Pitchlynn, 1830.” A Listening Wind: Native Literature from the Southeast. Ed. Marcia Haag. Nebraska UP, 2016. Pp 56-64.

Morgan, Phillip Carroll. “James L. McDonald’s Spectre Essay of 1830.” A Listening Wind: Native Literature from the Southeast. Ed. Marcia Haag. Nebraska UP, 2016. Pp. 43-56.

“Peter Pitchlynn 1864-1866.” Chiefs, The Choctaw Nation.

https://www.choctawnation.com/chief/1864-peter-pitchlynn