My Personal Journey with Dear Mr. Dickens

This post is contributed by Nancy Churnin, author of Dear Mr. Dickens.

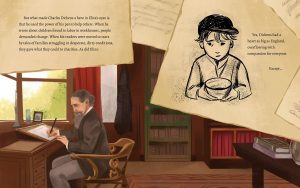

The question that propelled Dear Mr. Dickens, my children’s book which won the 2021 National Jewish Book Award, was how could a man as great-hearted and compassionate as Charles Dickens have created the ugly Jewish stereotype of Fagin in Oliver Twist?

It was a question that had troubled me since childhood – one that had driven a small rift between my mother and me. My mother, a teacher, who would go to any lengths to get me whatever book I wanted, hesitated when it came to Charles Dickens. She couldn’t comprehend how I could admire the man who created Fagin and questioned why I didn’t understand that stereotypes that portray Jewish people as thieves who prey upon children, only serve to exacerbate the antisemitism that led to the persecution of our people.

I couldn’t come up with an answer. My mom and our family had been through so much. Growing up in New York City, she was tormented by nightmares about her father’s family in Bialystok, Poland, who had not been able to gather the money or visas to come to America. Her father’s mother, two brothers, their wives, and children had been herded into a synagogue on June 27, 1941, which was burned to the ground along with hundreds of others (Jewish Historical Institute).

I would sneak off to read Dickens, sure that there had to be more to his story. I wished I could go back in time and write him a letter, letting him know how hurtful his characterization of Fagin was to the Jewish community – and ask him to do better.

Then, one day, as an adult, I found something that made me feel as though I had entered into another dimension. While doing research in Plano library, Texas in 2013, I skimmed through yet another article on Dickens and stopped when I read about Eliza Davis, a Jewish woman, who had written Dickens the very letter I had wished I could have written (Solomons).

The article quoted a few lines from one of the letters, but that was all. I asked the librarian where I could find the complete letters. She recommended three places – one in London where the original letters were, one in a distant state and one less than an hour from me in the University of North Texas rare book collection.

I called the librarian in the UNT rare book collection, who seemed delighted by my interest in the letters. He referred me to Professor J. Don Vann, the retired professor and Dickens scholar who had found the out-of-print book of letters, Charles Dickens and His Jewish Characters (1918) and donated it to the library. I called Professor Vann, made an appointment to have tea with him and his now late wife, the kind and caring Dolores Vann. The next thing I knew, the research librarian, at the direction of Professor Vann, had sent me photocopies of the letters in the book.

That was the start of an amazing journey. Through research that included a trip to The Charles Dickens Museum in London in 2014 and interviews with Dickens scholars Professor Murray Baumgarten, Distinguished Emeritus Professor at University of California at Santa Cruz and the late Professor David Paroissien, Professorial Research Fellow at University of Buckingham, England, and former editor of Dickens Quarterly, I learned that Eliza Davis was not the first to bring up the wrong she felt Dickens had done by making all his Jewish characters criminals. In fact, The Jewish Chronicle in London had asked in 1854, before Eliza Davis wrote her first letter, why “Jews alone should be excluded from the sympathizing heart of this great author and powerful friend of the oppressed”(Baumgarten 20).

Dickens brushed off the newspaper’s words. But it wasn’t easy for him to ignore Eliza. That’s because he knew and liked her. Eliza and her husband, James Davis, a banker, had purchased Tavistock House in London from Dickens in 1860. Dickens had assumed the purchase would be unpleasant because he would, after all, be dealing with Jewish people. He wrote to a friend, “If the Jew Money-Lender buys (I say ‘if,’ because of course I shall never believe in him until he has paid the money” (Letters 9: 307).

To Dickens’s surprise, the money was paid within a few days and the dealings were so pleasant that Dickens wrote to another friend, “Tavistock House is cleared today, and possession delivered up to the new tenant. I must say that in all things the purchaser has behaved thoroughly well, and I cannot call to mind any occasion when I have had money-dealings with anyone that have been so satisfactory, considerate, and trusting” (Letters 9: 303).

Dickens’s solicitude towards Eliza may have given her the confidence to follow up with a letter asking him to contribute to a fund to endow a convalescent home for the Jewish poor. In that same letter, she asked the question that he’d refused to answer from The Jewish Chronicle. Eliza wrote: “It has been said that Charles Dickens the large-hearted, whose works plead so eloquently and nobly for the oppressed of his country…has encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew” (Baumgarten 64).

Dickens responded to Eliza, but took issue with her criticism, saying that he had also written about criminals that weren’t Jewish. My book shows how Eliza persisted by writing a second letter, pointing out that while he had criminals that weren’t Jewish, all his Jewish characters were criminals and that didn’t represent Jewish people as they are.

And here’s where the story takes on both historical and personal power for me. Eliza opens Dickens’s eyes to how that characterization exacerbates the prejudice Jewish people face in England at that time. Not only did the English have a tradition of treating Jewish people badly – expelling them in 1275, two centuries before they were expelled from Spain during the Inquisition – and forcing Jews older than seven to wear a large yellow badge of felt shaped like the tablet of the Ten Commandments on their outer clothing, but even in Eliza’s time, Jewish people were expected to live in restricted areas, were unwelcome in trade guilds, and weren’t allowed to serve in Parliament (Byrne).

After Eliza’s letters, Dickens changed the way he writes about Jewish people. He created his first good Jewish character, the kindly Mr. Riah in Our Mutual Friend. In the middle of the 1867 reprint of Oliver Twist, he tried to change references to Fagin as “the Jew” (Meyer 240) – but the printer had already finished Chapter 38, so those changes aren’t seen until Chapter 39. He even admitted that Jewish people have “too long been wronged by Christian communities” (Dickens, 1866 qtd. in Bloom).

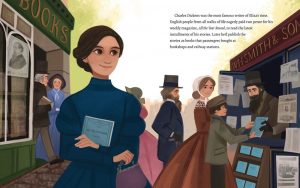

Dickens wielded great power with his pen. The readers of Oliver Twist, from chimney sweeps to Queen Victoria, wept for how children were treated which in turn led to the introduction of labor laws that protected children. Once he started speaking up for the Jewish community, attitudes began to change. He wasn’t the only one making a difference, but there’s no question that he played a key role in changing hearts and minds.

It was a deeply emotional moment for me when Dear Mr. Dickens was finally published in 2021 and I could put it in my mother’s hands. I had written this book because I had hoped to show children that like Eliza, they could make a difference by speaking up even to someone they admire, when that person is doing something wrong, to persist even if their first approach is rebuffed, and then, ultimately to forgive with love when that person makes amends.

But I had also hoped to show my mother, whose heart had been so wounded by antisemitism in her youth that people are capable of learning, changing, and doing better. My love for Charles Dickens had created a small, painful wedge between us. When she read this book, that wedge dissolved. Her eyes filled with tears. She read it over and over. It had restored her faith that she had once thought was gone forever that people are really good at heart. We hugged, once again feeling the same hope for the world.

Nancy Churnin’s Dear Mr. Dickens, illustrated by Bethany Stancliffe, published by Albert Whitman & Company in October 2021, is the winner of the 2021 National Jewish Book Award, a 2022 Sydney Taylor Honor Book, on the Best Informational Books for Young Readers list of the Chicago Public Library, and on the Best Jewish Children’s Books list of Tablet Magazine.

Dear Mr. Dickens is featured in the educational programming of The Charles Dickens Museum in London, in a collaboration with The Jewish Museum of London.

For more information on the educational program at The Charles Dickens Museum, click here: https://dickensmuseum.com/blogs/overseas/virtual-explorer-tour-with-dear-mr-dickens

For a free teacher guide, resources, and a DEAR… project, encouraging kids to write letters to people in positions of influence, visit Nancy Churnin’s website here: https://www.nancychurnin.com/dearmrdickens

Works Cited

Baumgarten, Murray. “’The Other Woman’ – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens.” Dickens Quarterly. 32. 1 (2015): 44-70. https://dickens.ucsc.edu/resources/pickwick-club/pdfs/the-other-woman–eliza-davis.pdf

Bloom, Cecil. Charles Dickens Anti-semitism. Web. < https://jewishcurrents.org/charles-dickenss-anti-semitism>

Byrne, Philippa. Why were the Jews expelled from England in 1290? Web. <https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/::ognode-637356::/files/download-resource-printable-pdf-5>

Clark, Cumberland. Charles Dickens and His Jewish Characters. London: Chiswick Press, 1918. Print.

Davis, Eliza. “To Charles Dickens.” 22 June 1863. In “Fagin and Riah.” Dickensian. 17 (1921): 144–52.

Dickens, Charles. ed. “Mr Whelks in the East.” All the Year Round. July 21 (1866): 31-35.

Jewish Historical Institute. 80th anniversary of the massacre of Jews in Białystok. Web. <https://www.jhi.pl/en/articles/80th-anniversary-of-the-massacre-of-jews-in-bialystok,512>.

Meyer, Susan. “Antisemitism and social critique in Dickens’s Oliver Twist” Victorian Literature and Culture. 33.1 (2005): 239–252.

Solomons, Israel. “Charles Dickens and Eliza Davis.” Miscellanies. (Jewish Historical Society of England) 1 (1925): iv-vi. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/29777057>

Storey, Graham, ed. The Letters of Charles Dickens, 12 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997. Print.

This was fascinating. My book club, meeting tomorrow, will be discussing A Tale of Two Cities. I am leading the discussion i will be certain to bring up this interesting detail of Dickens’ life. Thank you!