Escape to the country: Dickens in rural England

This post is contributed by Catherine Peck, a PhD research student in English Literature at the University of Surrey. Her research explores the cultural and social history of the English country cottage and how it is represented in nineteenth-century literature. Her research is supported by an AHRC Technē Doctoral Training Partnership Studentship. She can be found on Twitter at @cjpeck

Charles Dickens’s novels are best known for their city scenes, capturing the disparities between rich and poor amid overcrowded Victorian streets. Despite this dominant urban theme, Dickens’s work also includes many rural scenes, from country estates to cottage communities. In his personal correspondence, Dickens frequently mentions taking walks and excursions in the country, and the success of his literary career enabled him to purchase Gad’s Hill in 1856, tucked away in the beautiful Kent countryside. Given Dickens’s interest in the country, it would seem no surprise that it should also feature in his writing. However, his fictional representation of rural England is often conflicted. Across his work, Dickens’s country scenes shift between picturesque portraits of green beauty, to rural poverty and hardship equal to his grim city scenes. In a single chapter in Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop, published in 1841, both perspectives vie for his readers’ attentions.

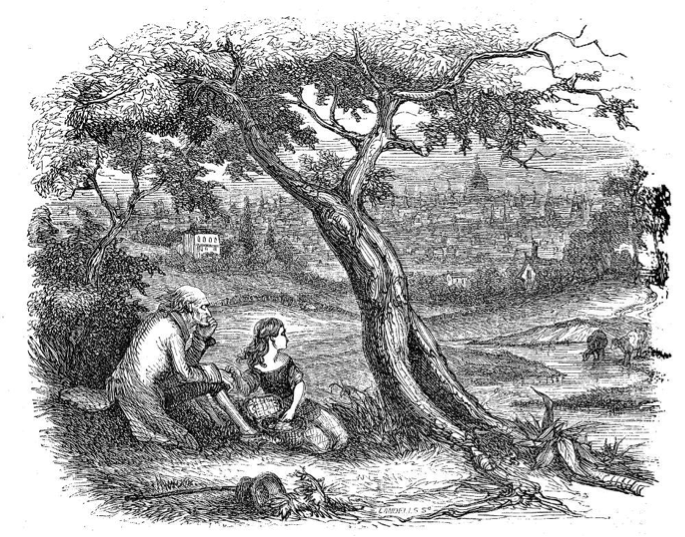

Within Victorian cultural ideology, there was a clear distinction between rural and urban spaces. Developments in machinery and production were transforming towns and cities into bustling centres for industry, business and trade, where overcrowding, crime and poverty plagued the rapidly expanding urban population. The city, as Jan Marsh observes, was viewed to be “physically and morally corrupting,” while the country offered “[h]ealth and happiness” (4). Idyllic perspectives of the country were facilitated by numerous forms of art and literature throughout the century, particularly landscape paintings which captured the peaceful beauty of nature and rural life (Figure 1).

In Chapter 15 of The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens creates a vivid transition from city to country that encapsulates these opposing perspectives and promotes the restorative appeal of the country. Hurrying through the city in the early hours of morning, Little Nell and her grandfather pass through “the haunts of commerce and great traffic” and “a straggling neighbourhood, where the mean houses parcelled off in rooms, and windows patched with rags and paper, told of the populous poverty that sheltered there” (122). What a relief it must have been for the travellers to finally emerge from these dismal London quarters and rest in “a pleasant field” and glance back “at old Saint Paul’s looming through the smoke” (123). At this border between city and country, Dickens defines both the physical and mental restorative effect the countryside has upon the weary city dwellers: “The freshness of the day, the singing of the birds, the beauty of the waving grass […] – deep joys to most of us, but most of all to those whose life is in a crowd or who live solitarily in great cities as in the bucket of a human well, – sunk into their breasts and made them very glad” (123).

The accompanying illustration by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) highlights this contrast (Figure 2). With London at a safe distance, Nell and her grandfather are seated in apparent rural bliss, a picture that could easily be the basis for a large oil and canvas painting bursting with healthy green hues (specifically works by William Holman Hunt). Cows amble over the rolling fields, and rural buildings are, as Dickens writes, “very few and scattered at long intervals, often miles apart” (125), rather than crammed together in London’s streets. To the right of the picture is a little rustic cottage – a seemingly minor detail, but a significant subject in cultural attitudes. The cottage, generally a small rustic dwelling, has long been associated with idyllic perspectives of the countryside. During the nineteenth century, the cottage was valued as a nostalgic symbol of a pre-industrial “Old England” (Maudlin 5), embodying the traditional cottage communities, culture and vernacular architecture feared to be diminishing under the advance of modernity. This admiration for the cottage manifested in various ways during Dickens’s time: cottages could be favoured as rural retreats for the wealthier classes, and rural labourers’ cottages were featured in art as examples of idealised country life (Clayton-Payne 10).

Dickens, however, disrupts this image by revealing the poverty experienced by many labouring cottagers in the second half of Chapter 15. Continuing on their journey, Nell and her grandfather occasionally pass “a cluster of poor cottages, some with a chair or low board put across the open door to keep the scrambling children from the road, others shut up close while all the family were working in the fields” (125). As Nell enquires at these cottages for rest and food, she witnesses problems in each impoverished home: “Here was a crying child, and there a noisy wife. In this, the people seemed too poor; in that, too many” (126). Nell thus discovers that suffering is not only an urban concern, but also a rural one. While industrial expansion increased the urban population, the rural population declined. Traditional agriculture and country crafts struggled to compete with new machinery, mass production and overseas goods, forcing farmers and labourers into the cities in search of work (Marsh 3-4). Among the remaining rural working-class population, struggling families crowded into dilapidated cottages or crude huts, where poor sanitation presented a constant risk of sickness (Clayton-Payne 17-18). The relief Nell feels in the “freshness” (Dickens 123) of the country air is thus dampened by these scenes of struggle.

Although Dickens’s descriptions of rural hardship in The Old Curiosity Shop are not as extensive as his corresponding urban scenes (particularly his bleak portrayal of the manufacturing town in Chapter 44), these brief passages in Chapter 15 present a side of rural life that disrupts the idyllic perspective of the countryside. In the space of one chapter, Dickens depicts not only a stark distinction between the urban and rural, but also differing conditions within the countryside itself. Rural poverty continues to be a frequent sight on the travellers’ journey and in Dickens’s other works. Despite his enjoyment of leisurely country walks, Dickens was clearly aware that Victorian rural life was not so picturesque or carefree for everyone.

References

Clayton-Payne, Andrew. Victorian Cottages. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1993.

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop. Penguin, 2000.

Marsh, Jan. Back to the Land: The Pastoral Impulse in England, from 1880 to 1914. Quartet Books, 1982.

Maudlin, Daniel. The Idea of the Cottage in English Architecture, 1760-1860. Routledge, 2017.