“He may just go to the Devil”: The Stormy Collaboration of Dickens and Cruikshank

This post has been contributed by Laurena Tsudama.

In a letter to his publisher John Macrone on October 19, 1836, the young author Charles Dickens wrote:

“I have long believed Cruikshank to be mad; and his letter therefore, surprises me, not a jot. If you have any further communication with him, you will greatly oblige me by saying from me that I am very much amused at the notion of his altering my Manuscript, and that had it fallen into his hands, I should have preserved his emendations as ‘curiosities of Literature.’ Most decidedly am I of opinion that he may just go to the Devil; and so far as I have any interest in the book, I positively object to his touching it.” (Letters 183)

In this quote, Dickens refers to a letter that Macrone received from George Cruikshank, Dickens’s illustrator at the time. In the letter to Macrone, Cruikshank writes that he did “expect to see that Ms. [of the “Second Series” of Sketches by Boz] from time to time in order that I might have the privilege of suggesting any little alterations to suit the Pencil” (Letters 183n). The disturbance Dickens expresses here at the idea of anyone other than himself “altering,” or authoring, is a feeling that would only increase with time.

Dickens is well-known for his dictatorial relationships with the artists who illustrated his novels. They were driven hard to fulfill Dickens’s vision of what the illustrations ought to be and how they should best reflect his writing. As the minute details and lively description characteristic of his novels indicate, Dickens often had a distinct impression of the illustrations that would accompany his writing. In a letter to his friend and, later, biographer John Forster, Dickens writes of his creative process that “some beneficent power shows it all to me, and tempts me to be interested, and I don’t invent it – really do not – but see it, and write it down” (Selected Letters 90). As an author for whom visualization was a foundational part of the writing process, Dickens perceived illustrators as potentially interfering with his vision. The only avenue for Dickens to ameliorate, if not solve, this problem was to curtail his illustrators’ freedom and ensure that they followed his text closely and listened to his myriad instructions.

However, when he collaborated with Dickens, Cruikshank was a more respected artist than any of Dickens’s later illustrators—at the time, his fame was nearly on par with Dickens’s. That factor, in addition to his unruly temperament, allowed Cruikshank considerable freedom when compared to that given to later illustrators. As a result, his illustrations to Dickens’s work occasionally diverge from the text, both in the details of the scenes he illustrated and the style in which he drew them. For Oliver Twist, Dickens attempted to keep Cruikshank’s work in line with his text, but not all aspects of Cruikshank’s individual approach and style could be banished. Dickens was concerned that illustrations at odds with his text would unduly influence readers’ perception of his novels, potentially undermining his vision of the text and the interpretation he wished readers to draw from it. Cruikshank’s increasingly caricature-like, theatrical mode of illustration clashed with Dickens’s growing desire to be seen as a sophisticated, literary writer, and this issue ultimately contributed to the breakdown of their professional relationship following their collaboration on Oliver Twist.

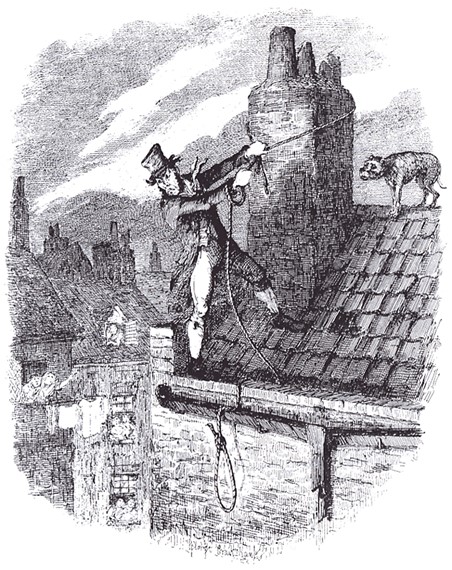

Dickens’s letters to Cruikshank regarding Oliver Twist typically refer to passages that he felt were suitable candidates for illustration. For example, on October 13, 1837, he wrote to Cruikshank: “I think you will find a very good subject at page 10, which we will call ‘Oliver’s reception by Fagin and the boys’” (Letters 319). Cruikshank appears to have complied with most of Dickens’s directives. One notable exception is the case of “The Last Chance,” Cruikshank’s illustration of Sikes’s final attempt at escape. Dickens felt that it “would not do for illustration,” being “so very complicated, with such a multitude of figures, such violent action, and torch-light to boot, that a small plate could not take in the slightest idea of it” (Letters 440). Note Dickens’s concern that an illustration would be unable to conform fully to his text. Dickens felt that no plate was needed because any attempt would necessarily deviate from the scene as described in the text. As can be seen in any edition containing the original illustrations, Cruikshank successfully illustrated the scene. However, he did find it necessary to stray somewhat from Dickens’s description of the moments leading up to Sikes’s death.

Action is grouped and frozen in “The Last Chance.” Because he drew the design despite Dickens’s belief that the scene would be too complicated for illustration and, presumably, did so without any more guidance from Dickens than the text itself, this illustration can be thought of as being especially the product of Cruikshank’s imagination. The scene in the novel progresses very quickly, yet Cruikshank chose to depict Sikes in a moment of pause and reflection as he looks toward the ground. Dickens writes that Sikes “set his foot against the stack of chimneys, fastened one end of the rope tightly and firmly round it, and with the other made a strong running noose by the aid of his hands and teeth in almost a second” (Oliver Twist 412). In the text, there is no time for Sikes to stand looking out at the prospect because he begins lowering the loop over his head and inadvertently hangs himself immediately after fashioning his means of escape. In the illustration, he is shown tightening the rope around the chimney after he has made the noose, which is a reversal of the events’ order in the text. Another detail that deviates from the text is the visibility of Sikes’s dog, who was hidden from both Sikes and the crowd, prior to Sikes’s death. The elements of the scene that Cruikshank removes from the text’s timeline and groups into this image serve to reference, in a fixed moment, the events that mark the entirety of the scene: Sikes’s frantic movement of his hands, his disturbed state of mind evident in his expression and afar glance, his impending doom signified by the hanging noose, and the dog’s inextricability from Sikes’s character as shown in its appearance on the roof. Cruikshank enhances the effect of this arrangement by stripping the scene of the crowd and the action occurring within the house, leaving this single tableau. Dickens’s text does not freeze in such a convenient expression of character as does Cruikshank’s illustration, and perhaps that better served Dickens’s intentions as an author. Indeed, Dickens’s growing desire to be taken seriously as a sophisticated writer, rather than a mere storyteller or public entertainer, eventually proved to be at odds with Cruikshank’s increasingly sensational, theatrical style. Perhaps their growing aesthetic divergence was one significant cause of the dissolution of their professional relationship.

After Dickens’s death in 1870, claims that Cruikshank had suggested and devised much of Oliver Twist’s plot were first made by Robert Shelton Mackenzie in an American periodical, and these claims were later corroborated by Cruikshank in a letter to The Times on December 30, 1871 (Harvey 199). John Forster, in his biography of Dickens, strove to refute these claims, and critics attributed Cruikshank’s protests either to his desire to restore his then-diminished fame or to the ramblings of an aging, fading mind. However, what these critics did not recognize is that Cruikshank was, in a sense, an author of Oliver Twist (though most likely not in the way he claimed) through his illustrations. Cruikshank’s plates are not mere mimesis of Dickens’s text, and many of the illustrated scenes deviate in both minor and major ways from how Dickens wrote them. The remnants of Dickens and Cruikshank’s professional relationship, from the texts they collaborated on, to their letters, to even Cruikshank’s later allegations, reveal that the authorship of Oliver Twist was dependent on the give-and-take inherent to writer-illustrator collaboration.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Vol. 1, edited by Madeline House and Graham Storey, Oxford University Press, 1966.

—. Oliver Twist. 1837–1839. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. Oxford University Press, 1999.

—. The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens. Edited by Jenny Hartley, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. Vol. 1, 9th ed., Chapman & Hall, 1872.

Harvey, John Roberts. Victorian Novelists and Their Illustrators. New York University Press, 1971.